Capturing history

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1971 Muktijuddho

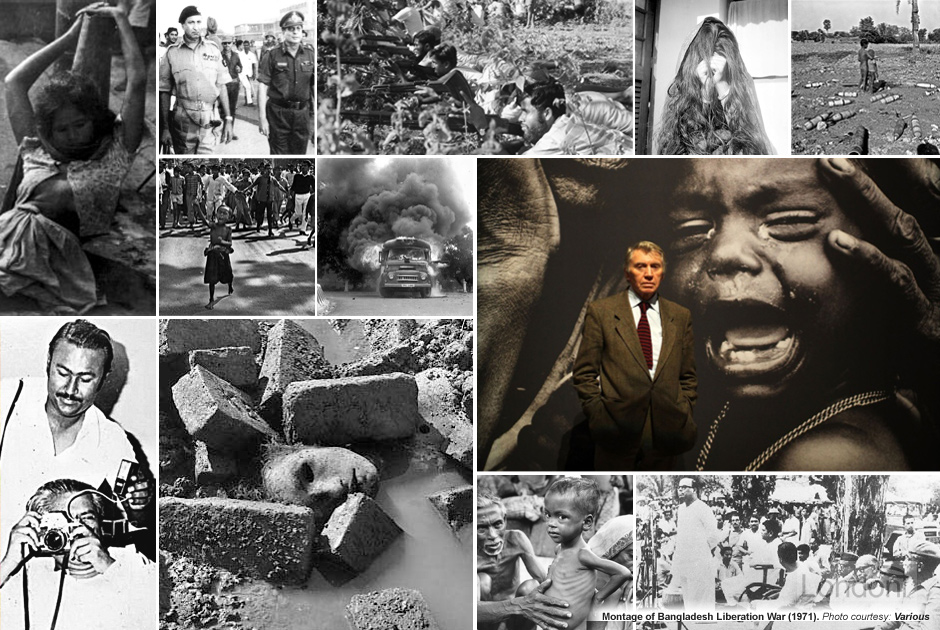

Most of the Bangladesh Liberation War photographers were young men and women who were then just starting out in the profession. Later becoming celebrated photographers of national and international repute, these daring souls and their camera were witnesses to the gore, misery and drama that are typical of war.

The photographers - both local Bengalis and foreign men and women from all over the globe - experienced all the movements within Bangladesh first hand. They snapped many historical incidents and were ready to face any tough situation.

To date, their photographs remain "the only physical documentation of the Swadhinata Juddho".

Bengali Photographers

Most of the Bengali photographers were self-taught, amateur photographers at the time - men who happened to be holding a camera when they found themselves caught up in the war. Born and brought up in the land, these Bengalis could smell and feel so many nuances and small details that a foreigner may not respond to. This gave them a greater understanding of the situation. There were no neat, studied frames in their photographs - just pure drama and emotion. Their photos radiated the shallowness of war with its multitude of elements, all of them falling perfectly in place.

Daring to risk their lives, these young and brave photographers were fuelled by passionate desire to preserve their history. They too were muktijuddhas. Armed with their camera, their passion was their bullet, their bravery their shield. Fighting to awaken the soul and conscience of man, they nullified their emotions, left behind loved ones, immersed themselves amongst their poor people to capture history as it unfolded in front of their eyes. "This will be our platform for seeking justice, one day, one day...", they thought.

This war was not about armies – this is a struggle where every civilian in Bangladesh was involved with in some way: farmers, everyday people, women.

As Bangladesh burned under Pakistani ravaging, from the ashes rose the golden generation of Bengali photographers - Rashid Talukder, Abdul Hamid Raihan, Naib Uddin Ahmed, Aftab Ahmed, Jalaluddin Haider, Mohammad Shafi, Sayeeda Khanom, Golam Mawla, Mukaddes Ali, to name but few. Each one a pioneer in their own right. Their photographs a piece of national treasure.

Their photographs are haunting - forever etched in memory. Most of the photographs are in black and white which "not only depicts the absence of colour photography but also the disparity of that dark time".

Their powerful and moving images provide a way of documenting the Liberation War and share both the tragedy and ecstasy of those turbulent days with future generations. It's a reminder of Bangladesh's glorious past, it's very own birth.

Rashid Talukder ()

Rashid Talukder ()  Abdul Hamid Raihan ()

Abdul Hamid Raihan ()  Naib Uddin Ahmed ()

Naib Uddin Ahmed ()  Aftab Ahmed ()

Aftab Ahmed ()  Jalaluddin Haider ()

Jalaluddin Haider ()  Mohammad Shafi ()

Mohammad Shafi ()  Sayeeda Khanum ()

Sayeeda Khanum ()  Golam Mawla ()

Golam Mawla ()  Mukaddes Ali ()

Mukaddes Ali ()

With a Kodak-127 camera Abdul Hamid Raihan started capturing images in 1946, framing portraits of friends, relatives and scenes of natural beauty. But his devotion to photography actually started when he bought a Yashica-635 in 1965 and made it his permanent company.

During the Liberation War in 1971, Abdul Hamid Raihan moved to India with his family. Leaving his family members in Karimpur, India he joined the liberation war with his the Yashica camera in hand. Till September14, 1971 he acted as an assistant in-charge of Karimpur recruitment camp which was known as youth camp or the feeder camp. Then, he joined the volunteer service core of the then Mujibnagar government as a photographer. There, his responsibilities were to capture the moments of our unconquerable fighters preparing for front wars as well as the devastations caused by the Pakistani soldiers and their local companions. The objective was to boost the morale of our suffering countrymen and to build public opinion in favour of our liberation war.

In less than three months, he framed about 500 photographs including the activities of the Mujibnagar government, training sessions of the freedom fighters, tortures of the Pakistani soldiers and war-torn areas. After the independence, he returned to Kushtia and established `Rupantor Studio'. But the moments and the memory of 1971 and the images he captured still remains deep inside his heart and at the age of 75 he nurtures it as his own child.

I grew up amidst the Second World War. In 1968, I bought a Yasaki camera and started taking pictures. In 1970, Bangabandhu visited Kushtia and that was the first time I took photos of Sheikh Mujib. The moment is forever etched in my mind. My lens captured various painful episodes during the Liberation War.

My father worked for the Railway Department and was transferred several times. There was no photographer in my family, so it was challenging for me to take up photography as a profession. Back in those days, the photo processing technology was rather poor. White was predominant after developing the images.

I love Bangladeshi villages and the villages love me back. When I was a child, I wanted to be a painter. In 1941, one of my maternal uncles gave me a baby brownie camera from Calcutta (now Kolkata). I developed the films myself.

After completing the Matriculation, I got admitted at Calcutta Islamia College in 1943. During that time, I had opportunities to meet Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, Shilpacharya Zainul Abedin and Patua Quamrul Hassan.

Art is the expression of emotions. This expression can be articulated through literature, painting, film or any other medium. I pre-selected some of the subjects of my photography - children, shepherds, peasants, potters, women, riverine life, green horizons etc. The beauty of nature and the simple lives of people attracted me the most. I have tried to capture the beauty of 'Bangla' in my own way. I left photography in 1971 as the brutality meted out by the Pakistani army affected me profoundly.

Rashid Talukder’s photo of the dismembered head in Rayerbazar, or the Pullitzer winning image by Michel Laurent and Horst Faas, of the bayoneting of Razakars have been used to represent Bangladesh’s war of liberation. Kishor Parekh photographed a different war. An old man held up a tiny flag of the new Bangladesh. A child cast a furtive glance at a corpse in the street. Jubilant children laughed as they ran across mustard fields in bloom. Women shed silent tears. "Shoot me right now, or take me", he had said to the major who refused to take this unaccredited photographer. But Parekh did board the helicopter, but then went his own way. On his own, with limited film, Parekh photographed the war that ordinary women, men and children had fought.

When [Sayeeda] Khanum started her photographic journey, society was not so friendly towards women stepping out of the home. She overcame this bigotry and paved a way for us.

Roksana Islam on how Sayeeda Khanum was more than 'just' a photographer

In the 1950’s, it was rare to see a woman carrying a camera in East Pakistan (as Bangladesh was then called). But Sayeeda Khanam had been photographing since 1940, when at age 13 she received from her sister the gift of a Rolleicord twin-lens reflex camera—which she still owns. “The different colors of the skies, the beauty of the Padma River, different birds” inspired her, she says, but later she turned to journalism. In 1956 she participated in an international exhibition in Dhaka, becoming the country’s first female professional photographer. In 1971, during Bangladesh’s War of Liberation, she took a photo of two rows of young women dressed in white saris with rifles on their shoulders. The image became one of the most famous photographs of the war.

[On her journey Sayeeda says] "I have tried to document time, space, society and history. It has not been so silky-smooth".

In 1959...a young man called Amanul Haq came to meet us. He was a photographer who believed there could be no subject as interesting as Manik [family name for Satyajit Ray]. He wanted permission to photograph him. He was well-spoken, warm and friendly. We liked him and Manik easily granted him permission...In no time at all, he had become part of the household. Manik grew very fond of him. He was a genuinely good photographer and even now never fails to visit us every time he comes to Calcutta...Only he has photographed my mother-in-law, Manik, Babu (Ray's son Sandip) and I. Babu together. Babu was very young at the time and grew very close to Amanul.

A few years after Amanul's arrival, yet another photographer from Bangladesh, a woman this time, came to our Lake Temple Road house. She was called Sayeeda Khanum but we know her by her nickname Badal....She still comes loaded with gifts to meet us on each visit. They are such lovely people and I'm grateful to them for not having forgotten us after Manik's death (in 1992).

Satyajit Ray's wife Bijoya on Bengali photographers Amanul Haq and Sayeeda Khanum