Introducing... Liverpool

Located on the north-western coast of UK where the river Mersey meets Irish Sea is the maritime mercantile city of Liverpool, once the Second City of British Empire. As the main port for the world's biggest colonial power, it was the location of mass movement of people, including slaves and emigrants from northern Europe to America and beyond. It is also a centre for innovation.

Liverpool's iconic waterfront is the face that the city projected to the rest of the world. It is a pioneer in the development of modern dock technology, transport systems and port management, and building construction which has had worldwide influence.

Liverpool's rise from a tiny insignificant hamlet to global domination of maritime trade, fuelled by its notorious role in the transatlantic slave trade, has given it a chequered reputation. As a major commercial port at the time of Britain's greatest global influence, it contributed to the development of the British Empire and became a world trade centre. It attracted people from all over the world who have contributed to the rich social fabric of the city. Liverpool can boost of having the oldest Chinese community in Europe, the oldest African community in UK, a large Irish population, and a mixed community including Bengalis, Arabs and Somalians making up its nearly half a million population - all of whom are identified as 'Scousers' or 'Liverpudlians'.

An extensive period of growth and innovation in architecture and cultural activities during the 19th and early 20th centuries gave way to sharp slump post the Second World War. Declining industries, recession, high unemployment and social problems led to a fast deterioration of this once powerful city. Music and arts provided solace during the 1960s.

Today, Liverpool shines at the heart of the European cultural scene, gaining multiple accolades ranging from UNESCO World Heritage Site status (2004) to European Capital of Culture (2008). It has the second largest collection of listed buildings in UK after London and is well-endowed with museums and galleries and a rich artistic heritage.

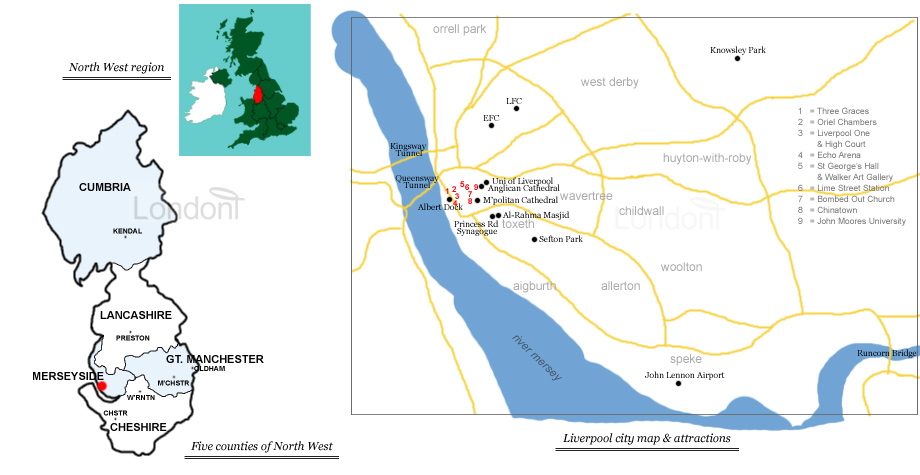

Map of Liverpool

Important information, tips, hints, ...ittadhi

- Liverpool city's official website: https://www.liverpoolairport.com

- John Lennon Airport telephone: +44 (0) 871 521 8484 (general enquiries)

- Royal Hospital telephone:

- Lime Street Railway: 0345 711 4141

- Police Control Room:

- Shops opening hours: 9am - 5pm everyday except Sunday when it's 11am - 4pm

- Coach station: Located in city centre next to John Lewis in Liverpool ONE

May Allah bless Liverpool and our People. Ameen.