Pre-Bhasha Andolon - ordinary people's fight to survive

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1952 Bhasha Andolon

The eastern wing of Pakistan, much smaller in size than the western wing, was densely populated and extremely poor. It was just over 15% the size of the western wing (Bangladesh's total area is 143,998 sq km, whilst Pakistan is 796,095 sq km) but had more people. And though Dhaka remained a prominent city, the government headquarters and the capital of the country (Karachi in 1947) were also in West Pakistan.

Thanks to this location of the bulk of political power and privilege in West Pakistan - its central bureaucracy was composed of 80% Pakistanis from other provinces mostly from Punjab - the Bengalis of East Pakistan faced systematic discrimination in every area of government employment.

The rulers from West Pakistan did not want to share power with the Bengalis and all the higher posts were invariably occupied by West Pakistanis, chiefly Punjabis who held a dominant share in the senior military and civilian jobs in 1947.

The leaders of the Muslims League thought that we (Bengalis) were a subject race and they belonged to the race of conquerors.

Ataur Rehman, a Bengali leader and Member of Constituent Assembly (MCA) declared in the assembly

Very little job opportunities and lack of investment in educational sector

The national budgets showed great disparities in terms of resource allocation and sector wise expenditure between East Pakistan and other provinces of Pakistan. Most foreign investment was directed into West Pakistan, and the largest share of international assistance was disbursed there.

In 1969-1970, East Pakistan, with a population of 75 million had 7,600 physicians, while West Pakistan with a population of 55 million had 12,400. Even in the educational sector, the number of colleges in West Pakistan grew from 40 to 271 between 1947 and 1969, whilst in East Pakistan this grew from 42 to 162.

Matters were no better in the elite Civil Service of Pakistan where, in 1948, only 11% were composed of Bengali officers. And this discrimination remained even until 1970 when the Bengalis only made up 16% of the civil service.

Their share in private business was also disproportionate – Bengali Muslims owned no more than 3.5% of the assets of all private Muslim firms.

| 1949-50 | 1959-60 | 1969-70 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| West Pakistan | 338 | 366 | 537 |

| East Pakistan | 287 | 278 | 331 |

| East-West gap | 51 | 88 | 206 |

Source: Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies

'Not a martial race' thus insignificant representation in national defence sector

The greatest discrepancy came in the military. It had less than 2% representation from East Pakistan and in 1948, out of 2,795 fresh privates, only 87 were Bengali.

Just before the 1965 war with India, East Pakistani men composed 6% of the army, 15% of the navy, and 16% of the air force. This was in large part due to the fact that the East Pakistanis were not considered to be a "martial race" – a British colonial notion where the Bengalis, seen as puny and 'naturally' rebellious intellectuals, were considered the black sheep of the Pakistani army.

East Bengalis who constitute the bulk of the population, probably belong to the very original Indian races. It would be no exaggeration to say that up to the creation of Pakistan, they had not known any real freedom or sovereignty. They have been ruled either by caste Hindus, Moghuls, Pathans, or the British. In addition, they have been and are under considerable Hindu cultural and linguistic influence. As such they have all the inhibitions of downtrodden races and have not yet found it possible to adjust psychologically to the requirements of new-born freedom.

Self-styled Field Marshall Mohammed Ayub Khan exemplifying the typical belief and contempt of the West Pakistani elite towards their Bengali-speaking Muslim brethren

The main effect of the language question was to exaggerate this growing sense of alienation in East Pakistan.

The main reason for opposition to Urdu was, however, not merely linguistic or even cultural. It was because Urdu was the symbol of the central rule of the Punjabi ruling elite that it was opposed in the provinces.

One explanation is that the Bengali salariat – people who draw salaries from the state (or other employers) and who aspire for jobs – would have been at a great disadvantage if Urdu, rather than Bengali, had been used in the lower domains of power (administration, judiciary, education, media, military etc). However, as English was the language of the higher domains of power and Bengali was a 'provincial' language, the real issue was not linguistic. It was that the Bengali salariat was deprived of its just share in power at the centre and even in East Bengal where the most powerful and lucrative jobs were controlled by the West Pakistani bureaucracy and the military.

Moreover, the Bengalis were conscious that money from the Eastern wing, from the export of jute and other products, was predominantly financing the development of West Pakistan or the army which, in turn, was West Pakistani- (or, rather, Punjabi-) dominated. The language, Bengali, was a symbol of a consolidated Bengali identity in opposition to the West Pakistani identity.

Dr. Tariq Rahman, Professor at Quaid-i-Azam University

Beginning of language controversy

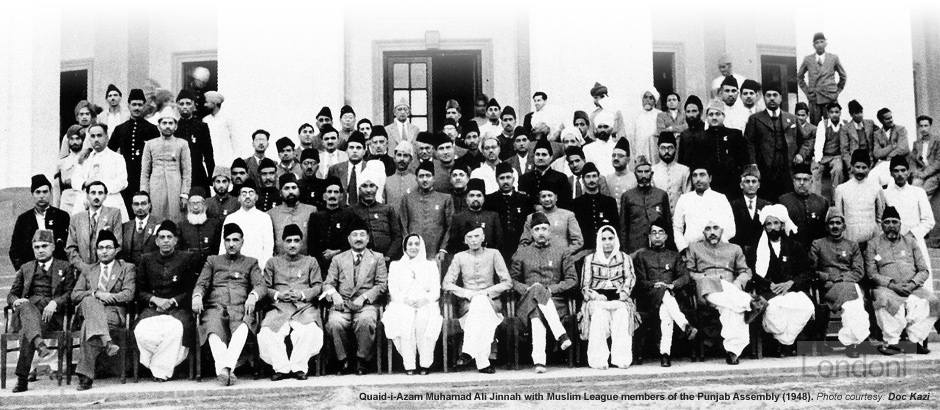

Roots of language controversy can be traced as far back as mid-19th century when Urdu was promoted as the language (lingua franca or working language) by political and religious leaders of Indian Muslims, especially by non-Bengali leaders for All-India Muslim League (AIML), popularly referred to as just Muslim League. The Uttar Pradesh-based Urdu-speaking stalwarts of the Muslim League had begun mobilizing their support and resources in favor of establishing Urdu as the lingua franca of Pakistan.

The Central Parliamentary Board of Muslim League prepared a 14-points Manifesto in June 1936 for the "protection and promotion of Urdu language and script". Another 25-points program was also designed for "setting out the special needs of Bengal" in 1936 by the same board. The board did not feel any need of adopting the Bengali language and script as Urdu-speaking leaders and their Bengali collaborators of Bengal Provincial Muslim League (BPML) supported the idea that "Urdu should be the official language of Bengali Muslims" as advocated in the 3 October 1937 Lucknow session of the Muslim League.

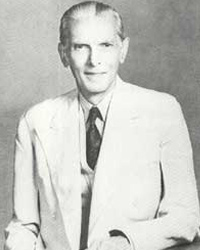

On this momentous occassion Muhammad Ali Jinnah, who was bestowed with the title of "Quaid-i-Azam" (Great Leader) for the first time at this session, propagated unity amongst the Indian Muslims whilst warning they’d be subjected to tyranny and hardship.

To the Muslims of India in every province, in every district, in every tehsil, in every town, I say: your foremost duty is to formulate a constructive and ameliorative program of work for the people's welfare, and to devise ways and means for the social, economic and political uplift of the Muslims…Organize yourselves, establish your solidarity and complete unity. Equip yourselves as trained and disciplined soldiers. Create the feeling of an esprit de corps, and the cause of your people and your country.

No individual or people can achieve anything without industry, suffering and sacrifice.

There are forces that may bully you, tyrannize over you and intimidate you, and you may even have to suffer. But it is going through this crucible of the fire of persecution which may be levelled against you, the tyranny that may be exercised, the threats and intimidations that may unnerve you - it is by resisting, by overcoming, by facing these disadvantages, hardships and suffering, and maintaining your true glory and history, and will live to make its future history greater and glorious not only in India, but in the annals of the world.

Muhammad Ali Jinnah tells Indian Muslims to be strong and united

Ironically, few decades later it would be the Muslims and Hindus of East (Purbo in Bengali) Pakistan who would embody the qualities that he is advising here against West (Poschim) Pakistan during Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971.

Nevertheless, many Bengalis started to voice their support for the Bangla language more publicly.

All-India Muslim League ()

All-India Muslim League ()  Muhammad Ali Jinnah ()

Muhammad Ali Jinnah ()

An ancient fight made new

The debate over the position and use of Bangla, the mother tongue of the people of Bengal, particularly of the Muslims, traces as far back as 17th century.

Muslim poet Abdul Hakim was the first litterateur to condemn in writing those Bengalis who looked down upon their own language. In his famous work "Nurnama" (Story of Light) - a depiction of the life of prophet Muhammad (Peace Be Upon Him) in lyrical Bengali, and considered as an important step in creating a Bengali Muslim identity - he wrote the poem "Bangobani" where he expressed his profound love for Bangla. In the poem, he criticised the Bangla detractors saying such people had no identity ('I cannot tell who gave birth to them') and urged them to change their attitude or to leave Bengal for good ('if one is not happy with his own language why doesn't he leave Bengal and go somewhere else'). Abdul Hakim's great patriotism fuelled him to promote Bangla at a time (medieval ages) when Persian and Arabic tended to be court languages all over South Asia and perceived by some as the literary language of choice.

"Bangobani" by Abdul Hakim

In 1918, Khan Bahadur Ahsanullah, an influential educationist and social reformer, expressed similar views to Abdul Hakim. In one of his writings, "Bangabhasha o Musalman Shahitya" (Bengali Language and Muslim Literature), he advocated the need to respect Bangla and recognise it over other languages such as Urdu.

Social welfare should ideally be the aim of literature...

A nation which does not have its own literature does not have self-esteem. The development of such a nation will always be a forlorn prospect. If one is to introduce oneself as a true Muslim and an equal to the rest of the world, then one has to uphold one's mother tongue with a nationalistic fervour. For restoring the very existence of the nation, the development of the Bengali language is a must.

Khan Bahadur Ahsanullah on the importance of mother language

Around the same time as Khan Bahadur Ahsanullah other social activists such as the Muslim feminist Roquia Sakhawat Hussain (aka Begum Rokeya) were choosing to write in Bengali to reach out to the people and develop it as a modern literary language. On 28 February 1927 - twenty five years before Ekushey February - two papers were presented on the second day of the two-day First Annual Literary Conference of the Muslim Sahitya Samaj (Muslim Literary Society) held in Dhaka. The papers discussed the role of Bangla in a Muslim society, specially in relation to education. Kazi Nazrul Islam inaugurated the Conference. Abul Hussain, the secretary and one of the founders of the Sahitya Samaj, wrote that the mother language barrier had been the major obstacle to the social development of the Muslim community in Bengal.

Abdul Hakim (1620 - 1690) Medieval Bengali poet. Knew several languages including Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit and thus had access to Persian texts as well as Sanskrit classics like Ramayana, Mahabharata, etc. Translated book include Yusuf-Zulekha (translation of the Persian romance Yusuf Wa Zulekha, 1483 AD), Nurnama (Story of Light) and Durre Majlish (a book of moral instruction translated from Persian). Original writings in Bangla include Lalmoti Saifulmulk (a romance, was published towards the end of the nineteenth century and immediately gained wide popularity) and Hanifar Ladai (manuscript still incomplete). Other work include Shihabuddinnama, Nasihatnama, Karbala, and Shahornama. Son of Shah Razzaque. Born on the island of Sandwip, off the coast of Noakhali.

Abdul Hakim (1620 - 1690) Medieval Bengali poet. Knew several languages including Arabic, Persian and Sanskrit and thus had access to Persian texts as well as Sanskrit classics like Ramayana, Mahabharata, etc. Translated book include Yusuf-Zulekha (translation of the Persian romance Yusuf Wa Zulekha, 1483 AD), Nurnama (Story of Light) and Durre Majlish (a book of moral instruction translated from Persian). Original writings in Bangla include Lalmoti Saifulmulk (a romance, was published towards the end of the nineteenth century and immediately gained wide popularity) and Hanifar Ladai (manuscript still incomplete). Other work include Shihabuddinnama, Nasihatnama, Karbala, and Shahornama. Son of Shah Razzaque. Born on the island of Sandwip, off the coast of Noakhali. Khan Bahadur Ahsanullah ()

Khan Bahadur Ahsanullah ()  Roquia Sakhawat Hussain (aka Begum Rokeya) (1880 - 1932)

Roquia Sakhawat Hussain (aka Begum Rokeya) (1880 - 1932)  Abul Hussain ()

Abul Hussain ()