'Bhasha' Matin convenes the Dhaka University Rashtrabhasha Sangram Parishad

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1952 Bhasha Andolon

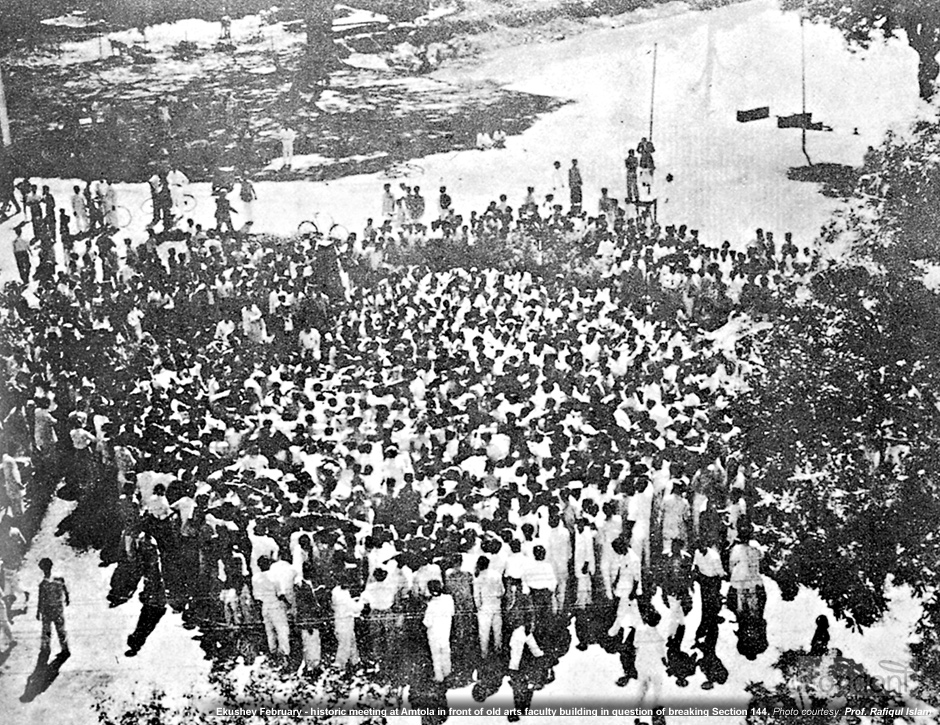

On 11 March 1951, a young and passionate Abdul Matin, who had famously stood on his chair and cried out "No it can not be!" when Muhammad Ali Jinnah declared Urdu as the state language at Dhaka University convocation, established the Dhaka University Rashtrabhasha Sangram Parishad (Dhaka University Language Action Committee). During a rally held at Dhaka University, organised by East Pakistan Chhatra League and presided by veteran student leader and President of the Chhatra League, Khaleque Nawaz Khan, Abdul Matin was selected as convener of the student action committee.

Abdul Matin (Born 1926) Bhasha Shoinik (Language Activist). Passed matriculation in Darjeeling School (1932). Enrolled in Rajshahi College. Graduated in International Relations at Dhaka University. Very active and influential during Bhasha Andolon. Famously shouted "No it can not be" when Jinnah declared Urdu as state language, convened the Dhaka University Rashtrabhasha Sangram Parishad, and encouraged students to defy Section 144 during Ekushey February. Recipient of Swadhinata Purushkar (1997, along with Dhirendranath Datta), Mother Teresa Gold Medal (2010) and Geetanjali Honorary Award (2012) . Awarded with honorary Doctor of Law degree along with ANM Gaziul Haq by Dhaka University in 2008 - it was the first time DU had awarded an honorary degree to a language veteran.

Abdul Matin (Born 1926) Bhasha Shoinik (Language Activist). Passed matriculation in Darjeeling School (1932). Enrolled in Rajshahi College. Graduated in International Relations at Dhaka University. Very active and influential during Bhasha Andolon. Famously shouted "No it can not be" when Jinnah declared Urdu as state language, convened the Dhaka University Rashtrabhasha Sangram Parishad, and encouraged students to defy Section 144 during Ekushey February. Recipient of Swadhinata Purushkar (1997, along with Dhirendranath Datta), Mother Teresa Gold Medal (2010) and Geetanjali Honorary Award (2012) . Awarded with honorary Doctor of Law degree along with ANM Gaziul Haq by Dhaka University in 2008 - it was the first time DU had awarded an honorary degree to a language veteran.

The student community of Dhaka University had actively opposed the various policies and ploys of the then Central Government of Pakistan from the beginning of the language issue in 1947. The initial strong reaction to the language issue was confined to the students of Dhaka University and it was they who were the most vociferous and active during the Bengali Language Movement.

Abdul Matin convened the student action committee to organise resistance against the constitutional conspiracies of the Muslim League government of Pakistan and to positively direct the energy and activities of the most enlightened segment of the students. For his endeavours and passionate commitment to the cause - which continued throughout his life - Abdul Matin became more popularly known as 'Bhasha Matin' (Language Matin). It was through his and nameless many others selfless and courageous acts that Bangla was eventually safeguarded and established as the marti bhasha (mother tongue) of the people of Bangladesh.

I was introduced to Bangla alphabets by my father. One day he brought me an Adarshalipi book, chalk and chalk board. I was told to learn the alphabets. As I gazed upon the Bangla alphabets, I noticed that every single alphabet was connected to each other. Alphabets as 'Ba', 'Raa', 'Ka', 'Bargiyo Ja', 'Anthiyostha' and so on are quite familiar to each other.

I developed a liking for the alphabets from my early age and I requested my father to send me to a Bangla school.

I often used to wonder about language and its function. I realised that it is the most powerful medium as we express ourselves and communicate with each other through language.

...And so, we moved forward and in the years that followed we organised the Language Movement and today everyone can speak Bangla without any restriction.

The Purba Pakistan Jubo League was formed just two weeks after the Dhaka University Rashtrabhasha Sangram Parishad was formed. Once again, student leader Abdul Matin played a prominent role in finding this organisation and he was selected as Joint Secretary of the Jubo League. Matin was also a key member of the central committee of the East Pakistan Chhatra League which, along with the Jubo League, was an Awami League front and instrument of the nationalist movement. However, after objecting to the Chhatra League's decision to select Sheikh Mujibur Rahman as it's Chairman, Abdul Matin was promptly fired from the committee.

Abdul Matin attended a key session of the Shorbodolio Rashtrobhasha Kormi Parishad and went on to convene the DU Language Action Committee, organisations which drew support from East Pakistan's student and intellectual communities and the wider middle-classes for the recognition of Bangla as a state language, mobilising endorsement of the view that Bengalis were a distinct segment of the Pakistani polity which merited acknowledgement and respect from the Karachi-based state.

S. Mahmud Ali, author of "Understanding Bangladesh" (2010)

Memorandum to Constituent Assembly in 1951 warns of repercussion

After convening the Dhaka University Rashtrabhasha Sangram Parishad, Abdul Matin submitted a historic memorandum to the Constituent Assembly in Karachi, Pakistan, highlighting the need to declare Bangla as a state language. The memorandum, given in 1951, turned out to be the basis of historic Language Movement one year later.

We, the students of Dhaka University, who initiated the language movement in East Bengal three years ago who are now more determined than ever to secure for Bengali the status of state language of Pakistan, will take this opportunity, while you are all assembled at Karachi, to press once more our legitimate claim.

The movement is going to be pretty old and it is unfortunate to state that while our whole energy should be harnessed in nation building activities, the Central Government in refusing to accept Bengali as a prospective state language has created distrust and apprehension in the minds of the majority of Pakistani people.

The apprehension is legitimate and until and unless it is removed it is sure to alienate a people without whose whole-hearted co-operation the dreams of unity and solidarity will never materialise.

Out of the Principle of self-determination came Pakistan and the young state is still struggling to achieve freedom in the real sense of the term. To be completely free, materially and intellectually, a long way is still to be traversed and as one of its first obstacles the formidable weight of English language is to be lifted to make room for languages of the people. No free people can afford to neglect its mother tongue which alone is efficient to help develop the intellectual faculties inherent in every man. The domination of an alien language is the worst kind of domination and most efficient to keep a people servile; and the British knew this when they ousted Persian and introduced English in the early part of the nineteenth century.

...The Central Government is still to declare its policy clearly and categorically. It will be committing the greatest mistake if, in selecting the state language, it goes against the principles of democracy.

When the state has only one language the problem is simple. When it has many, the question of preference arises. If the language spoken by the majority is also sufficiently developed and has a good literature it can without hesitation be accepted as the state language. If the linguistic minorities are clamorous we have several state languages, as in Canada and Switzerland.

In the case of Pakistan the obvious choice is of course Bengali. It is the language of the majority (56% per cent of Pakistan’s population are Bengali speaking) and it is the richest language not only of Pakistan but of the whole of Indo-Pakistan sub-continent. It has a history over thousand years old and it has a wonderful vitality to develop and absorb foreign influences. In the last hundred years its development has been phenomenal and it draws its nourishment from the sap of the soil. Not only that, it has its intricate roots of connection with Sanskrit, Hindustani, Urdu and Persian. It is also the language which has most completely absorbed the sprit of Western literature. Basically Eastern in origin, it is of all the languages of the sub-continent the most modern and western in outlook.

Urdu, which is being favoured by the Centre, perhaps because some of the important men in the ministry and in the Secretariat happen to be Urdu speaking, offers poor contrast to Bengali. It is not the mother tongue of any of the provinces of Pakistan and is equally alien to Bengali, Panjabi, Sindi, Baluch and Frontier men. Urdu is a symbol of saying culture. It has hardly any foothold and it is doubtful whether it could survive without princely patronages. Even Iqbal, the dreamer of Pakistan and the great Urdu poet of the century found it inadequate for his difficult thoughts. In writing his great philosophical poem ‘Asrar-i-Khudi’ he had to discard Urdu in favour of Persian and he frankly admits. Because of the loftiness of my thought Persian alone is suitable to them.

Such a language whose efficacy as the state language is very much doubted from political and linguistic points of view and which presents formidable obstacles in the way of printing cannot be the state language of Pakistan.

Several points are urged in favour of Urdu-from interested quarters. It is claimed to be an Islamic language. We refuse to believe that any language under heaven can be Islamic or Christian or Heathen. If Urdu is Islamic, Bengali is equally so. Nay, it is more Islamic as a larger number of Muslims speak Bengali. Secondly Urdu is urged to be the uniting factor between the different provinces of Pakistan. If this is to mean that Urdu can serve as the lingua franca between the multilingual provinces then nothing could be more absurd as it is equally foreign to all the Parts of Pakistan. A lingua franca is always a natural historical growth; it is never the artificial creation of a government.

Thus neither as an Islamic language which is absurd nor as the lingua franca which is fictitious, can Urdu claim to be the state language of Pakistan.

In spite of all this if Urdu is accepted as the only state language, it is sure to give rise to serious problems. (1) It will create a privileged class in the same way as English did because it will not be possible for the vast majority who do not speak Urdu to master it overnight. This will facilitate the way of exploitation of the many by the few. (2) It will nourish disaffection among Pakistanis in general and Bengalis in particular, and it will strike at the root of national integrity without which there is no future for our country. Thirdly and lastly the material and intellectual development which all go to enrich the national culture will be jeopardised. A people must learn and think in its own language. To deny one one’s natural language is to deny everything. And to rob a people of its language is to render freedom a myth.

Lastly, we have only to repeat what we have made clear time and again. If Pakistan is to have only one state language is must be Bengali, if more than one, Bengali must be one of them. We are at a loss how this simple logic to fail to penetrate the brains of our leaders. There must be some thing wrong somewhere. Otherwise this unjust and stepmotherly attitude of the Centre towards the province of the golden fiber is difficult to explain.

The dreamers of Karachi deaf to the groan of the starving primary school teachers of East Bengal are squandering thousands of rupees over Arabic Centres in the province. They are lending every possible support to Urdu with the food. Hope that someday it will replace English and are playing the mischievous game of imposing Arabic script over Bengali. We, the students of Dhaka University, claiming the immediate implementation of the provincial policy in the matter of language and demanding Bengali to be the state language of Pakistan have given a tough fight and are prepared to fight to the last. We shall never accept Urdu as the only state language. We are sworn to expose the great conspiracy which aims at reducing East Bengal to the state of a colony.

We remind them and the peoples representatives who are at the helm of the affairs that until and unless the claim of Bengali is fully established in the province as well as in the Centre, the students of Dhaka University shall not rest.

Abdul Matin's historic memorandum to the Constituent Assembly in Karachi in 1951