Pakistan's new Governor-General Khwaja Nazimuddin maintains Urdu stance

Last updated: 5 October 2017 From the section 1952 Bhasha Andolon

Bengali Khwaja Nazimuddin becomes the 2nd Prime Minister of Pakistan after Liaquat Ali Khan assassinated

As the year 1951 progressed, Liaquat Ali Khan was assassinated whilst addressing a public meeting in Rawalpindi on 16 October 1951. His assassin was swiftly pounced upon by a mob and killed on the spot. To this day, it has never been made clear as to who were behind the murder of Pakistan's first prime minister.

Liaquat announced a five-day tour of Punjab, and as he was about to deliver a public address in Rawalpindi on 16 October 1951 he was shot at close range. His assassin was killed on the spot by a police inspector, who was also shot nine years later, leaving no direct witnesses or proof of conspiracy. It is widely believed that a conspiracy had taken the life of Quaid-i-Millat (Leader of the Nation), Liaquat Ali Khan. Some believe that Daultana and Gurmani had lured the prime minister to give a public speech in Punjab to sell the parity formula to the Punjabis himself, as they would not do it, and were in some way involved with the assassination. Ghulam Mohammad, the Finance Minister, and Gurmani were both in Rawalpindi on the day of the assassination, thus feeding the rumour mill about their likely complicity. Some speculated Liaquat was planning to remove Ghulam Mohammad from his cabinet post, thereby providing a motive for him.

Yasmeen Niaz Mohiuddin, author of "Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook" (2007)

The Bengalis could not dispel a fear that Liaquat had been killed because he leaned toward the east, and that in silencing the prime minister, their voices too had been muted... Bengalis were convinced that high members of the central and Punjab governments were implicated in Liaquat's death.

Lawrence Ziring, author of "Pakistan in the Twentieth Century: A Political History" (1999)

Three days after Liaquat Ali Khan's death, on 19 October 1951, Khawaja Nazimuddin resigned from his Governor-General role and stepped down to take over as the country's second prime minister, believing that he was needed to save the nation at a difficult time. Ghulam Muhammad, the Punjabi Finance Minister, became the new Governor-General of Pakistan. But Nazimuddin inherited an impossible legacy of reconciling opposite views on constitution making. The problems in the air only got worse.

His [Khwaja Nazimuddin's] assumption of this office and occupation of this position was due to his life long collaboration with non-Bengali group of the Muslim League. His tenure was characterized by failures, conspiracies and timidity. It was noted that he followed those policies that were to survive in the power structure of Pakistani politics at any cost. He himself dealt with the committed pro-Bengali language activists and demonstrators as the Chief Minister of East Pakistan in 1948. But he did not take any bold step either to resolve or revisit the language issue and his government introduced reforms through a six years educational program for making Urdu as the State language and educational system on basis of Islamic Ideology.

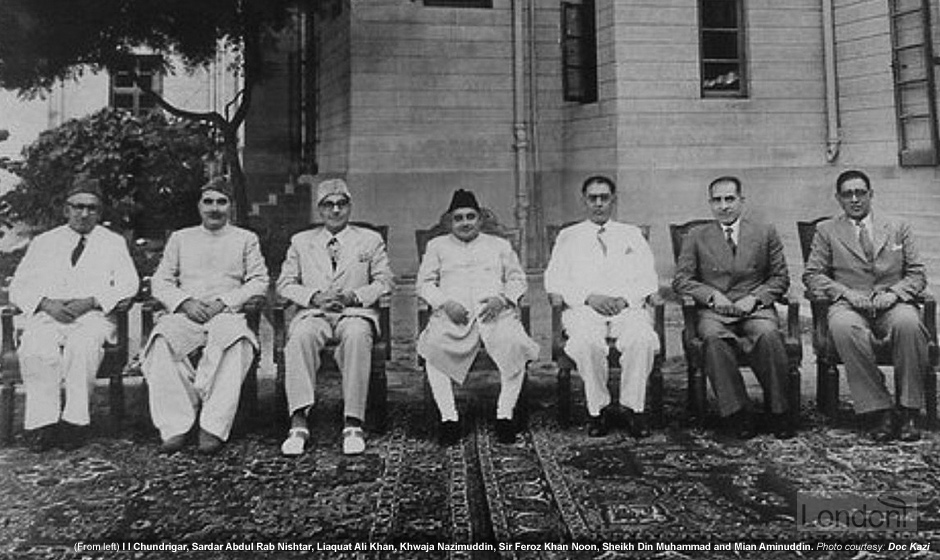

Liaquat's assassination before his government could draft a constitution plunged Pakistan into seven years of political chaos and led to a collapse of the parliamentary system. After his assassination, there were six prime ministers in seven years: Khwaja Nazimuddin (17 months), Mohammed Ali Bogra (29 months), Chaudhry Mohammed Ali (13 months), Shaheed Suhrawardy (13 months), I. I. Chundrigar (2 months), and Firoz Khan Noon (11 months). During this period, two bureaucrats, Ghulam Mohammad and Iskander Mirza, brazenly abused their powers as head of state to make or break governments. As politicians and bureaurcrats bickered and quarrelled and were unable to govern, the military became increasingly involved and finally took over.

To fill the post left vacant by Nazimuddin, Gurmani proposed the name of Ghulam Mohammad, the finance minister, on the grounds that because of his failing health he would be a ceremonial head of state and would not threaten the prerogatives of the prime minister. Nothing could have been further from the truth, as events would prove in the next few years. Ghulam Mohammad's promotion to governor general was a strategic maneuver by Chaudhri Mohammad Ali and Gurmani, encouraged by many civil and military officials, including General Ayub Khan, as well as some Punjabi politicians, to bypass Nazimuddin and in time to discredit and finally drive him from office.

...The governor general and the prime minister made a very odd couple. Ghulam Mohammad, an aggressive and self-confident Punjabi bureaucrat, detested politicians and wanted to rely more on the civil bureaucracy. Nazimuddin, like Jinnah, believed in a single, unified Pakistan, and in Urdu as a unifying language, even though it was not his mother tongue, thereby putting national interests above personal and provincial interests. None of the consitutional issues were resolved; instead a series of events took place that eventually led to the collapse of the parliamentary system. Ghulam Mohammad centralized authority in his person, dominating Nazimuddin and making a shambles of the office, causing great harm to the nation.

Yasmeen Niaz Mohiuddin, author of "Pakistan: A Global Studies Handbook" (2007)

But Nazimuddin was not privy to the machinations of clever politicians, both east and west, who were intent on destroying his provincial power base... Nazimuddin had become a target of the power-brokers.

Lawrence Ziring, author of "Pakistan in the Twentieth Century: A Political History" (1999)

Declaration of Urdu as state language in Paltan Maidan, Dhaka

In the beginning of 1952, the language controversy took a serious turn. Both Jinnah and Liaquat Ali Khan were no more in this world to resolve the issue and newly-appointed prime minister Khawaja Nazimuddin was not in position to handle the issue properly. People of East Bengal were critical about the anti-Bengali policy of Punjabi and Mohajir dominated ruling class.

Amidst all the tension, Prime Minister Nazimuddin reignited the Urdu-Bengali controversy at the Paltan Maidan, Dhaka session of the ruling Muslim League party on 27 January 1952 by repeating the Quaid-i-Azam’s view that "Urdu will be the state language of Pakistan", as also noted in the report of the Basic Principles Committee. Nazimuddin flew in from Karachi to Dhaka and, addressing the public meeting presided over by Chief Minister Nurul Amin, said that the people of the province could decide what would be the provincial language, but only Urdu would be the national language of Pakistan. He also stated that at the initiative of the government Bangla will be written in Arabic script.

This declaration [by prime minister Khwaja Nazimuddin] was in direct opposition to the promise he had made to the students four years earlier, and was tantamount to snapping his fingers at the previous year's census figures, which had indicated that a majority - 56.4% - of the Pakistani population declared Bengali to be their mother tongue, while the figure for Urdu had dropped to only 3.37%.

Christophe Jaffrelot, editor of "A History of Pakistan and Its Origins" (2002)

Interestingly, Nazimuddin could not speak Bangla since Urdu was the language spoken in the Dhaka Nawab family and Bangla was not his mother tongue. Nevertheless, he delivered the speech in Bangla but as he was not proficient enough in the language the speech was written for him in Urdu script by Mizanur Rahman, a senior Bangali government official in Karachi.

His declaration came as a shock even to his colleagues. Both chief minister Nurul Amin and general secretary of the East Pakistan Muslim League Yusuf Ali Chowdhury (Mohon Mian), who sat beside Nurul Amin on the dais, confessed that "no one in the ruling circles was aware that Nazimuddin would make such a statement" and especially in that manner. Nurul Amin declared that he had "no idea about the content" and was irritated that the prime minister had "converted a dormant issue into a live issue".

We had absolutely no previous knowledge of what Nazimuddin was going to say in his Paltan speech and both Nurul Amin and I after hearing the speech were absolutely stupefied.

In the course of (Nazimuddin's) lengthy speech from a written script, he mentioned that Urdu shall be the state language. The statement was not only uncalled for but also inconsistent with the stand of the Muslim League members of the CA (Constituent Assembly) from East Pakistan and the assurances received from a section of their counterparts from the West...

The prime minister seemed to have been so effectively briefed from interested quarters that he kept such an inflammable issue a guarded secret from me even and did not have the courtesy to consult me... I was sitting on the dais where he was speaking from and as soon as he uttered the sentence I could foresee its consequences. When I charged him after the meeting, he told me that the brief was prepared in Karachi.

Syed Badrul Ahsan, Journalist

Even Aziz Ahmed, the first Chief secretary of East Bengal and a Punjabi who was known for his anti-Bengali views, told Nurul Amin that he had not seen the text of the Prime Minister's speech, but if he had, he would have advised Nazimuddin against making his remarks on the state language issue.

I knew nothing about this matter but afterwards when Nazimuddin asked me if I had seen the script of the speech before. When I said 'no', he said that he had instructed his private secretary to show it to him. Had I seen it I would have definitely advised him not to make this speech.

Chief Secretary Aziz Ahmed who was the representative of Karachi in Dhaka

-- [profile] Aziz Ahmed Foreign Secretary in the Ayub Khan regime. Minister of state for foreign affairs under Zulfikar Ali Bhutto's leadership. ---

Comments spark off wave of protests throughout East Bengal

Reaction to Khwaja Nazimuddin's declaration was swift and largely devastating. The announcement triggered off the language controversy once again and a new phase of Bengali language movement was inaugurated with greater strength after all the frustrations of those who had realised how little importance Karachi attached to the aspirations of East Bengal. The people who had prepared Nazimuddin's speech had provided the disgruntled politicians and public of East Bengal with more ammunition as the language issue was too potent to be neglected.

Two days after the speech, on 29 January 1952, the Dhaka University State Language Committee of Action called a meeting on the campus to censure Nazimuddin over his comments. They put up a number of posters on display all over the campus protesting against the treacherous remarks of the Prime Minister. For his part, Oli Ahad, then general secretary of the Youth League, severely condemned Khwaja Nazimuddin in a press statement that was carried by all newspapers in the provincial capital.

The next day, the East Pakistan Muslim Students' League called a meeting at Dhaka University where they severely criticised the governor general over his remarks and renewed the call for Bangla to be adopted as a state language of Pakistan. It also reminded Nazimuddin of his earlier promise, made when he was chief minister of East Bengal, that Bangla would be accorded the status of state language of Pakistan. Once the meeting was over, the student activists marched to the residence of the chief minister at Burdwan House (today's Bangla Academy), where they chanted a number of slogans in favour of Bangla. They also called for a province-wide in all educational institutions on 4 February 1952.

Having felt the fury of an agitated province, Nazimuddin tried to later redeem himself by insisting that he did not express his personal opinion when he urged that Urdu must become the lingua franca of the nation. What he had done was merely to quote from the Quaid-i-Azam and he said even that statement had been included in his speech as one item among so many others.

The Prime Minister complained that "a twist had been given to my speech about the State language and it was made to appear as an expression of my opinion." He chose to add that the matter was not a "live issue" and that discussion should cease. But Nazimuddin's protests fell on deaf ears; the language controversy was a potent weapon in the hands of those who wanted to destroy the East Bengal Muslim League, and those who would wield it prepared their strategy.

Aziz Ahmad & Karigoudar Ishwaran, editors of "Contributions to Asian Studies, Volume 5" (1971)