A leading figure during Bhasha Andolon

Last updated: 6 October 2017 From the section Dr. Muhammad Shahidullah

A passionate Bengali

In 1911 a number of young Muslim writers including Mohammad Maniruzzaman Islamabadi, Dr. Muhammad Shahidullah, Mohammad Yakub Ali Chowdhury, and Mohammad Mozammel Huq founded the Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Samiti (Bengal Muslim Literary Society), a literary organisation of Bengali Muslims. Dr. Shahidullah was elected secretary of the organisation.

Mohammad Maniruzzaman Islamabadi ()

Mohammad Maniruzzaman Islamabadi ()  Mohammad Yakub Ali Chowdhury ()

Mohammad Yakub Ali Chowdhury ()  Mohammad Mozammel Huq ()

Mohammad Mozammel Huq ()

Inspired by the Bangiya Sahitya Parishat (1893), the organisation was influenced by the rising Muslim separatist trends. Its objectives included cultivation and preservation of Bangla literature, writing biographies of pirs and dervishes, encouraging Muslim writers, and establishing harmony between Hindus and Muslims. It arranged monthly meetings and annual conferences. Of the seven literary conferences arranged by it, five were held in Kolkata, while one was held in Chittagong and another in Bashirhat. It published two journals: Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Patrika (Literary magazine of the Muslims of Bengal, April 1918), in which many of the writings of Kazi Nazrul Islam were published, and Sahityik (December 1926).

As the organisation's secretary Dr. Shahidullah presided over many meetings and conventions, including the second Bengal Muslim Literary Convention (1917), Muslim Literary Society Convention in Dhaka (1926), All-Bengal Muslim Youth Convention in Calcutta (1928), All-India Oriental Studies Convention (Philology, 1941) and East Pakistan Literary Convention (1948). He also represented UNESCO at the International Seminar on Traditional Culture in South-East Asia in Madras and was elected its chairman.

Shahidullah was an academician. Academic activities like some plants best thrive in seclusion. Shahidullah had enjoyed a secluded life of a University teacher. Unlike their modern counterparts the University teachers in those days did not enjoy media exposure. Without either being romantic or sentimental one can say that those were the days of plain living and high thinking. Shahidullah loved a contented life of a University teacher and a researcher. However, he was also aware of the fact that a social being he had other duties to discharge. So whenever situation demanded he came out of his cloistered life and joined hands with the populace. Thus on many occasions he came out in the open to take issues with the Government.

In April 1941 Sher-e-Bangla A. K. Fazlul Huq inaugurated the jubilee celebrations of the Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Samiti while Kazi Nazrul Islam presided over it. The seventh and final annual conference of the organisation was held in May 1943. The importance of the organisation decreased with the formation of the East Pakistan Renaissance Society (1942) in Kolkata and the Purba Pakistan Sahitya Sangsad (East Pakistan Literary Society, 1942) in Dhaka.

In addition to being an exemplary academic and cultural activist, Dr. Shahidullah was also a renowned literateur. His writings on language, literature and culture were published in many magazines and newspapers, and he himself edited many such publications. He worked as an associate editor of Al-Eslam (Islam, 1915) and was joint editor of Bangiya Mussalman Sahitya Patrika (1918-21). He edited and published the first children's magazine of Muslim Bengal, Angur (Grapes, 1920). Also, he edited a monthly called The Peace (1923), the monthly literary magazine Babgabhumi (The land of Bengal, 1937) and the fortnightly Taqbir (Call, 1947).

A. K. Fazlul Huq (Sher-e-Bangla) ()

A. K. Fazlul Huq (Sher-e-Bangla) ()  Kazi Nazrul Islam ()

Kazi Nazrul Islam ()

The fight to save Bangla and Bengali identity

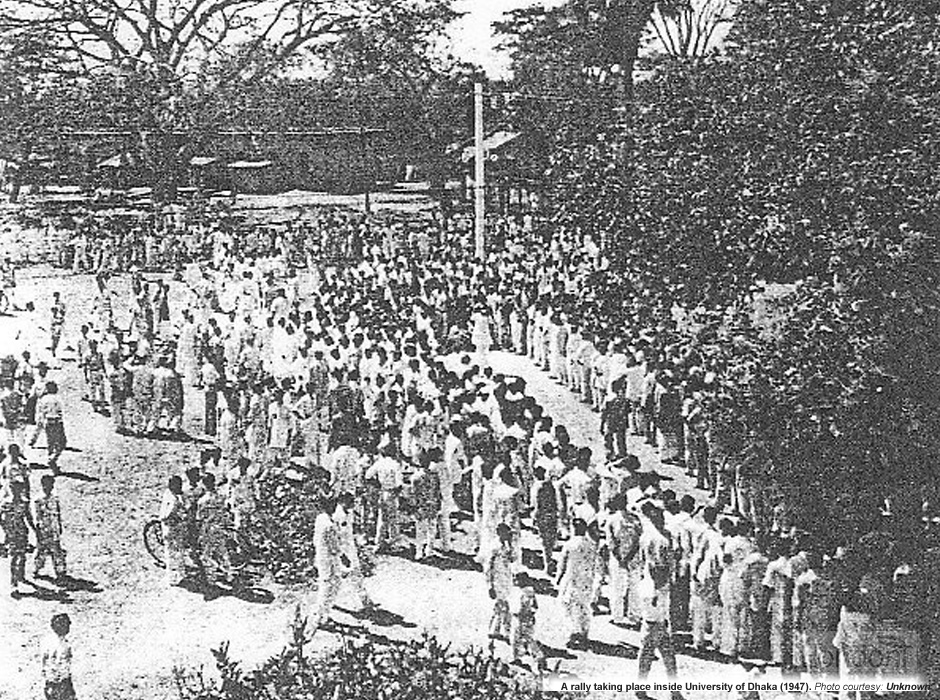

In 1947 British India was partitioned along religious lines into India (with mainly Hindu populace) and Pakistan (mainly Muslims). The province of Bengal, with almost equal sized religious populations, was divided with the western third joining India and the eastern two thirds becoming East Pakistan. In the years that followed, Bengali linguistic and cultural nationalism became the dominant political force as the residents of East Pakistan were increasingly marginalised in the Pakistani political process. The Language Movement of 1947-1952 had engulfed the eastern wing of Pakistan.

In the early 50s there was unrest among the people of the then East Pakistan. The majority of the people were Bangla-speaking. The people of East Pakistan demanded Bangla as the state language. During the time, the situation was terrible, with arrests and torture of intellectuals, students and politicians by the Pakistani regime. The Dhaka University campus became the focal point for student meetings in support of Bangla.

During this testing time - it was the first national crisis to erupt in newly formed Pakistan - Dr. Shahidullah played a critical role in promoting the Bangla language. As the first chair of the Bengali Language Department at the University of Dhaka Dr. Shahidullah researched on the origins of Bangla and wrote extensively on the language. Along with being a practising Muslim he was a passionate Bengali and was at the forefront of the movement to establish Bengali, in addition to Urdu, as a national language of Pakistan. Dr. Shahidullah was the first to publicly establish the reasons why Bangla, instead of Urdu, should be the state language of East Pakistan. He also spoke against the 'Arabization' of Bangla language which would have resulted in Bangla being written in Arabic script.

"We are Bengali"

Dr. Shahidullah presided over the 'Purbo Pakistan Sahitya Shommelon' (East Pakistan Literary Conference), the first of its kind to be organised since the setting up of the Pakistan state, held in Dhaka over two days on 31 December 1948 and 1 January 1949. In his presidential speech at the concluding session of the conference Dr. Shahidullah made it clear that Bangla being a rich language qualified as the medium of instruction in East Pakistan. Echoing the sentiments that Rabindranath Tagore had expressed over four decades earlier in his 'Eka' (Alone) song - also popularly referred to as 'Ekla Chalo Re' (Go Forth Alone) song - during the Partition of Bengal in 1905, Dr. Shahidullah reminded everyone that East Pakistan was the land of both the Muslims and the non-Muslims. But it was more significant that the land belonged to the Bengalis.

In an address to a literary conference in 1929, Shahidullah described his Islamic identity as being more important than his Bengali linguistic heritage. He suggested that the pan-Islamic community was more important than local place-based attachments in defining identities. By 1948, however, in his presidential address to the East Pakistan Literature Conference, he argued that East Pakistani literature should be written in Bengali and that links should be maintained with the Bengali speaking communities in India. He concluded by acknowledging that part of their identities were defined as Hindu and Muslim, but that it was truer that they were all Bengali.

Reece M. Jones, author of "Bounding Categories, Fencing Borders: Exclusionary Narratives and Practices .." (2008)

In East Bengal, as the writings and speeches of A. K. Fazlul Huq and Muhammad Shahidullah attest, there was a fundamental rethinking of the association between place, religion, and identity during the middle of the 20th century. During this period many people began to question whether religious connections alone were enough to bind populations together and instead a common, place-based Bengali heritage was emphasised.

Reece M. Jones, author of "Bounding Categories, Fencing Borders: Exclusionary Narratives and Practices .." (2008)

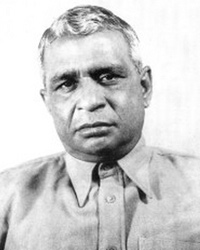

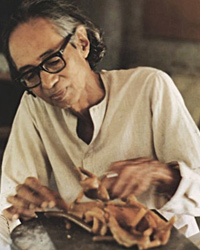

Son Murtaja and other youngsters inspired into action by Dr. Shahidullah

Along with Dr. Shahidullah the fight to save Bangla language and, more importantly, Bangla identity were being taken up by many other proud sons and daughters of the Bengal soil. Young people such as Prof. Abul Kashem, MP Dhirendranath Datta, Kamruddin Ahmed, Prof. Abul Mansur Ahmed, Abdul Matin, and countless more made active efforts to establish Bangla as a state language and preserve its long and rich heritage. Dr. Shahidullah's son Murtaja Baseer was also one such ardent cultural activist. Murtaja was then a 20-year-old student in Dhaka Art College (now Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Dhaka) and actively participated in processions and protests to defend Bangla. The youngster joined in with other fellow artist and painted on walls, paper and canvas during the movement. They worked day and night and, against all odds, used their creativity to generate patriotic sentiments among the masses.

Abul Kashem ()

Abul Kashem ()  Dhirendranath Datta ()

Dhirendranath Datta ()  Kamruddin Ahmed ()

Kamruddin Ahmed ()  Abul Mansur Ahmed ()

Abul Mansur Ahmed ()  Abdul Matin ()

Abdul Matin ()

Being an activist of Student Federation, the then student wing of the Communist Party, Murtaja Baseer had been conscious and directly involved in the movement from the very beginning.

In 1950, I was in jail for involvement with the Communist Party. Abdullah- Al Muti-Sharfuddin, Ali Akshad, noted politicians Bari and Monu Miah were my cellmates. We were in room no 14. During the five months in jail, I wrote poetry. When I'm in jovial mood, I like to paint. When I'm depressed, I like to write.

I was then only a Class Nine student and used to live in Bogra as my father was the principal of Government Azizul Haque College there. In fact, the movement for establishing Bangla as an official language had begun just a few months after the partition of India in 1947, and I got involved in the movement in March, 1948.

In those days I used to write graffiti "jonotar kantho rodh cholbe na, rashtra bhasha bangla chai" (can't stop the voice of people, demanding Bangla as the state language). After I got admitted into the then Government Institute of Arts [now Faculty of Fine Arts of Dhaka University], I returned to Dhaka in 1949 and became active in the movement.

In the morning [of Ekushey February], students began gathering on the Dhaka University premises in defiance of Section 144. Subsequently, we gathered at the university gate and attempted to break the police barricade. Police fired tear gas shells towards the gate. We ran into Dhaka Medical College, and the intention was to reach the then East Bengal Legislative Assembly, which was opposite to Jagannath Hall, to ask the legislators to raise the issue in the assembly. Facing tear shell and baton charge, I along with Hafizur Rahman took position near a police barrack at the Medical College dormitory. All on a sudden, police fired on the mob.

Nearby I found a small crowd. Approaching there I found a bullet-hit well-dressed clean shaved man crying for water. Requesting the mob, he said, "I'm Abul Barkat please convey this message to my family at Paltan Line". We immediately took him to the emergency of the hospital. He was the first bullet wounded man although there were many injured people over there. While returning, we saw a dead body, which had been crashed by bullet. Later, we heard his name was Rafiq. Then found another body. Ahmad Rafiq said he was Salam.

After the tragedy of Ekushey February and its aftermath resulted in injury and death to many innocent youngsters in Dhaka, Bengalis throughout the region collectively raised in national uproar.

Shahidullah took pride in the fact that his students placed the Bengali language in the highest pedestial literally at the cost of their lives. He would understandably become sentimental when he had to speak on what had happened on that fateful 21st February [Ekushey February].

Shahidullah hated politics for the sake of it. He knew that politics was a dirty game. But he was bold and courageous enough to fight for any right cause even at the risk of being misunderstood. If such an attitude is considered political, Shahidullah was then a political man. The issue that became crucial was by no means 'political'. This was a very real identity crisis - a question of survival not only of a people but also of a cultural milieu. And here he was uncompromising. He allowed his youngest son Murtaja Baseer to participate in the movement launched on the 21 February 1952.

Murtaja's 'Parbe Naa' poem and 'Raktakto Ekushey' illustrations

Murtaja Baseer wrote a poem titled 'Parbe Naa' (You cannot) as his first artistic protest against the brutal incident. The powerful poem delved deep into patriotism and socialism. It was included in "Ora Pran Dilo" (They gave up life), a compilation of poems on the Bhasha Andolon, and published in the Baishakh issue of the Kolkata-based 'progressive' literary magazine Parichoy, edited by Subhash Mukhopadhyay in 1952. The magazine cover was designed from a linocut of Somnath Hore, a veteran Indian painter-sculptor.

Subhash Mukhopadhyay ()

Subhash Mukhopadhyay ()  Somnath Hore ()

Somnath Hore ()

I wrote the poem just after a few days of 21 February 1952, expressing the determination to endure pains to practice Bangla language. I sent the poem to Parichoy office in Kolkata. But I cannot exactly remember when I did the artwork which was the first protest by any artist through an artwork.

I heard that Artist Aminul Islam also claimed that he made a painting titled "Humanity Crucified" during the period. But, I never saw that on display nor even in the group art exhibition at the empty residence [now Bangla Academy] of the then chief minister of East Bengal Nurul Amin which was organised in 1954 after the Jukta Front Government took power.

Murtaja Baseer is by nature a shy and reclusive person. His poetry is innovative and original. His perception and discoveries form his poems.

Reading Baseer's poetry is like undergoing an emotional journey. As a poet, he is a modernist in the whole sense. His style is unquestionably unique, expressive and easily comprehensible. When readings his poems, one feels the yearnings of a lonely soul, unbound sorrow, the vacuum in a melancholic heart. Baseer's poems are voyages into fantasy.

After 'Parbe Naa' in 1952 Murtaja did not write a single poem for 20 years. Instead he turned to visual arts for inspiration.

When I was in Class X [10] in 1948, I started writing short stories. I was a student of Bogra Coronation Institution. During that time, I also wrote a play for my class.

I had published a collection of short stories called 'Kanch-er Pakhir Gaan' in 1969. Noted scholar and dramatist Shaheed Munier Chowdhury reviewed it on television. Munier Chowdhury told me, 'Your skill in narrating conversations is very good. You should write plays.

Murtaja collaborated with senior artist Bijon Chowdhury to further capture the tragedy of bloody Language Movement event in illustrations. The illustrations, a linocut and sketches, were published as 'Raktakto Ekushey' (Bloody 21st) in 1953 in a volume titled 'Ekushey February'. The publication was the first compilation work on the Language Movement and contained collection of poems, short stories, songs and essays. It was edited by Hasan Hafizur Rahman. However, in the publication only Murtaja's name was printed and Bijon Chowdhury did not receive any accreditation.

Bijon Chowdhury ()

Bijon Chowdhury ()

I and Bijon Chowdhury did all the illustrations, but the credit of the illustrator was given only to me. Maybe, his name had not been published anticipating, perhaps, that problem might be created by the Muslim League in power on the issue.

But I mentioned the fact in my earlier statement that more matured illustrations had been done by Bijan Chowdhury since he was a senior and I was not even introduced to figurative drawing when we did those artworks. Artistically, those illustrations could be not up to standard, but I of course claim those works have historical importance since those are the detailed documents from the witness to the whole movement.

Till date 'Raktakto Ekushey' remains one of the very few visual documentation of the events which happened during the language movement.