Repeal of 1972 Collaborators Act & execution of Colonel Taher leads to anger

Colonel Taher arrested 16 days after freeing Ziaur Rahman

On 23 November 1975, Ziaur Rahman ordered the arrest of JSD leaders, which included Colonel Abu Taher, the man who set him free 16 days earlier following his house arrest after Major Khaled Musharraf's coup d'etat. A large police contingent surrounded the house of Colonel Taher's brother, and Bir Bikram, Major Abu Yusuf Khan and took him to the police control room. When Colonel Taher found out about this he rang General Zia but was told that he was not available. Instead Major-General Ershad, the Deputy Chief Martial Law Administrator, spoke with him. When Colonel Taher informed Ershad regarding the arrest of his brother, Ershad said it was a police action and they knew nothing about it.

The next day Colonel Taher was arrested and taken to Dhaka Central Jail. He was accused of 'instigating indiscipline' in the army and attempting to expand the original mutiny of 7 November 1975 towards a goal of "socialist revolution" and to kill some of the army officers.

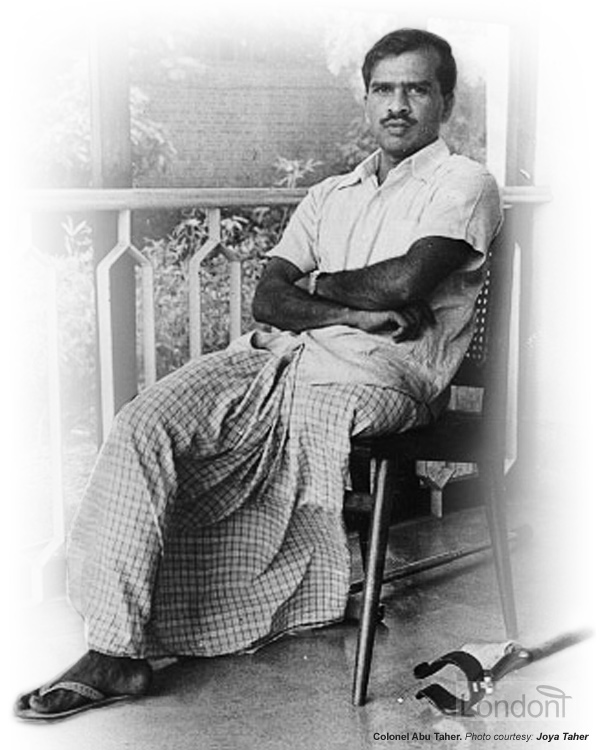

Abu Taher (14 Nov 1938 - 21 July 1976) Bir Uttam. Sector 11 (Mymensingh-Rangpur) Commander during 1971 Swadhinata Juddho, a military officer and left-leaning radical activist. Born in Badarpur in Assam, India. Paternal home Kazla village in Purbadhala thana of Netrokona district, Bangladesh. Graduated from Sylhet M. C. College (1959) and read up to MA preliminary level in Social Welfare and Research Institute under the University of Dhaka (1960). Served as an assistant teacher for sometime at Durgapur High School in Mirsharai thana of Chittagong district (1959). Joined Pakistan Army (1960) and transferred to Special Service Group (Commando force) in 1965. Fought in Indo-Pak War of 1965 first in Kashmir and then in Sialkot sector, and received gallantry award for his chivalry. Participated in a training course at Ford Brag and Ford Benning on guerrilla warfare in 1969, and obtained graduation with honours in higher war techniques. Also participated in the Senior Tactical Course at Quetta Staff College in 1970, but left in protest against genocide in Bangladesh by Pakistan army in 1971. In July 1971, he crossed the border from Abbotabad, Pakistan, along with Major Muhammad Abul Manzoor, Major Ziauddin Ahmad, and Captain Patwary and joined Swadhinata Juddho http://www.banglapedia.org/HT/T_0023.HTM. Appointed Sector 11 (Mymensingh-Rangpur) Commander. Seriously wounded and left leg blown off from above the knee while launching an attack on enemy camp at Kamalpur (known as the gateway to Dhaka) on 14 November 1971. Received medical treatment in India and returned to Bangladesh in April 1972. Honoured with Bir Uttam gallantary award for valour during Muktijuddho. Appointed Adjutant General of Bangladesh Army and made commander of 44th battalion and commanding officer of Comilla cantonment in June 1972. Joined politics in October 1972 and elected vice president of central organising committee of Jatiya Samajtantric Dal (JSD or Jashod for short). Organised Sepoy-Janata Biplob (uprising of the soldiers and public) on 7 November 1975 which freed Ziaur Rahman, then Chief of Army Staff, from house arrest. But arrested by Zia on 24 November 1975 and hanged to death in Dhaka Central Jail after a secret military tribunal. He became the first official political execution in independent Bangladesh.

Abu Taher (14 Nov 1938 - 21 July 1976) Bir Uttam. Sector 11 (Mymensingh-Rangpur) Commander during 1971 Swadhinata Juddho, a military officer and left-leaning radical activist. Born in Badarpur in Assam, India. Paternal home Kazla village in Purbadhala thana of Netrokona district, Bangladesh. Graduated from Sylhet M. C. College (1959) and read up to MA preliminary level in Social Welfare and Research Institute under the University of Dhaka (1960). Served as an assistant teacher for sometime at Durgapur High School in Mirsharai thana of Chittagong district (1959). Joined Pakistan Army (1960) and transferred to Special Service Group (Commando force) in 1965. Fought in Indo-Pak War of 1965 first in Kashmir and then in Sialkot sector, and received gallantry award for his chivalry. Participated in a training course at Ford Brag and Ford Benning on guerrilla warfare in 1969, and obtained graduation with honours in higher war techniques. Also participated in the Senior Tactical Course at Quetta Staff College in 1970, but left in protest against genocide in Bangladesh by Pakistan army in 1971. In July 1971, he crossed the border from Abbotabad, Pakistan, along with Major Muhammad Abul Manzoor, Major Ziauddin Ahmad, and Captain Patwary and joined Swadhinata Juddho http://www.banglapedia.org/HT/T_0023.HTM. Appointed Sector 11 (Mymensingh-Rangpur) Commander. Seriously wounded and left leg blown off from above the knee while launching an attack on enemy camp at Kamalpur (known as the gateway to Dhaka) on 14 November 1971. Received medical treatment in India and returned to Bangladesh in April 1972. Honoured with Bir Uttam gallantary award for valour during Muktijuddho. Appointed Adjutant General of Bangladesh Army and made commander of 44th battalion and commanding officer of Comilla cantonment in June 1972. Joined politics in October 1972 and elected vice president of central organising committee of Jatiya Samajtantric Dal (JSD or Jashod for short). Organised Sepoy-Janata Biplob (uprising of the soldiers and public) on 7 November 1975 which freed Ziaur Rahman, then Chief of Army Staff, from house arrest. But arrested by Zia on 24 November 1975 and hanged to death in Dhaka Central Jail after a secret military tribunal. He became the first official political execution in independent Bangladesh. Abu Yusuf Khan ()

Abu Yusuf Khan ()

It became very clear to me that a new conspiracy had taken control of those we had brought to power on 7 November 1975.

On 24 November 1975 I was surrounded by a large contingent of police. The police officer asked me to accompany him to have a discussion with Zia. I said I was surprised and I asked him why there was need of a police guard for me to go to Zia. Anyway they put me in a jeep and drove me straight to this jail. This is how I was put inside this jail by those traitors who I saved and brought to power.

In our history, there is only one example of such treachery. It was the treachery of Mir Zafar who betrayed the people of Bangladesh and the subcontinent and led us into slavery for a period of 200 years. Fortunately for us it is not 1757. It is 1976 and we have revolutionary soldiers and a revolutionary people who will destroy the conspiracy of traitors like Ziaur Rahman.

What is remarkable is that Khaleda Zia once regarded Abu Taher as a family friend. Taher used to visit her home and when Zia feared for his life on the morning of 7 November 1975, it was Taher he called.

Lawrence Lifschultz, Journalist

Prominent JSD members arrested

Security forces, searching for illegal arms, detained many JSD activists and sympathisers, forcing them into hiding. Besides Colonel Taher, 32 others, including 22 members of the armed forces, were to be put on trial on charges of attempting to overthrow the government of Bangladesh and of incitement of the armed forces towards mutiny. Most of the accused were connected with JSD or its military wing, the BGB and included civilians who were in detention after Sheikh Mujib's clampdown in 1974. Some of these leading personalities were Major M. A. Jalil (JSD President and Sector 9, Barisal-Patuakhali, Commander during 1971 Muktijuddho), ASM Abdur Rab (General Secretary of JSD and one of the first people to fly the Jatiyo Potaka or National Flag on March 1971), Hasanul Huq Inu (General Secretary of the Krishak or Peasants' League), Mohammed Shahjahan (President of the Sramik or Workers' League who also flew the Jatiyo Potaka alongside ASM Abdur Rab), and M. B. Manna (General Secretary of the Chhatra or Students' League).

Other notables among the accused included Major Abu Yusuf Khan, Prof. Anwar Hossain (Colonel Taher's younger brother), Major Ziauddin Ahmad, Serajul Alam Khan, Dr. Akhlaqur Rahman (a leading Bengali economist), and K. B. M. Mahmood (Editor of the English weekly 'Wave'). Saleha Begum was the only female amongst the accused.

In a futile attempt to free Colonel Taher, his brothers and other JSD cadres attempted to abduct the Indian High Commissioner in Dhaka so they can negotiate an exchange. However, this ended in bloody failure.

On 8 December 1975 Peter Custers, a Dutch journalist working for a Dutch news agency in Bangladesh since 1973, was also arrested on charges of plotting an armed revolution to overthrow the government.

M. A.(Mohammad Abdul) Jalil (9 Feb 1942 - 19 Nov 1989) Sector 9 Commander during 1971 Muktijuddo, distinguished freedom fighter and politician. Born in Wazirpur, Barisal district. Passed matriculation from Wazirpur WB Union Institution (1959) and IA examination from Murry Young Cadet Institution. Joined Pakistan Army as trainee officer in 1962. Obtained BA and MA in History during his service in the army. Promoted as Captain (1965) and Major (1970). Came to Barisal in February 1971 on army leave from his posting in Multan, Pakistan, and joined the Muktijuddho the following month. Appointed commander of Sector 9, but removed from this position in November. Floated new, left-leaning political party Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal (JSD) in October 1972. At the inception of the party he was the joint convenor, and was elected chairman of the party in the council session held on 26 December 1972. Under his leadership JSD tried to establish "scientific socialism" in the country and was active in anti-government politics. Contested from seven constituencies in the Jatiya Sangsad elections in 1973 with no return. Arrested while launching a programme of the party activists to besiege the official residence of the then Home Minister on 17 March 1974. Released on 8 November 1975. Re-arrested on 25 November by the martial law government for his alleged conspiracy for the overthrow of the government and attempts at usurping the state power. Sentenced to life long imprisonment (18 July 1976) in a trial by the special military tribunal. But released on 24 March 1980. Contested in the presidential election in 1981 as a nominee of the three-party alliance of JSD, Workers Party and Krishak-Sramik Samajbadi Dal. Removed from chairmanship of the JSD in 1984. Left JSD and floated a new party styled as Jatiya Mukti Andolan through which he launched a programme for Islamic movement. Author of many books on politics including: Seemahin Samay (1976), Dristibhangi O Jiban Darshan, Surjodoy (1982), Arakshita Swadhinatayi Paradhinata (1989), Bangladesh Nationalist Movement for Unity: A Historical Necessity. Died in Islamabad, Pakistan.

M. A.(Mohammad Abdul) Jalil (9 Feb 1942 - 19 Nov 1989) Sector 9 Commander during 1971 Muktijuddo, distinguished freedom fighter and politician. Born in Wazirpur, Barisal district. Passed matriculation from Wazirpur WB Union Institution (1959) and IA examination from Murry Young Cadet Institution. Joined Pakistan Army as trainee officer in 1962. Obtained BA and MA in History during his service in the army. Promoted as Captain (1965) and Major (1970). Came to Barisal in February 1971 on army leave from his posting in Multan, Pakistan, and joined the Muktijuddho the following month. Appointed commander of Sector 9, but removed from this position in November. Floated new, left-leaning political party Jatiya Samajtantrik Dal (JSD) in October 1972. At the inception of the party he was the joint convenor, and was elected chairman of the party in the council session held on 26 December 1972. Under his leadership JSD tried to establish "scientific socialism" in the country and was active in anti-government politics. Contested from seven constituencies in the Jatiya Sangsad elections in 1973 with no return. Arrested while launching a programme of the party activists to besiege the official residence of the then Home Minister on 17 March 1974. Released on 8 November 1975. Re-arrested on 25 November by the martial law government for his alleged conspiracy for the overthrow of the government and attempts at usurping the state power. Sentenced to life long imprisonment (18 July 1976) in a trial by the special military tribunal. But released on 24 March 1980. Contested in the presidential election in 1981 as a nominee of the three-party alliance of JSD, Workers Party and Krishak-Sramik Samajbadi Dal. Removed from chairmanship of the JSD in 1984. Left JSD and floated a new party styled as Jatiya Mukti Andolan through which he launched a programme for Islamic movement. Author of many books on politics including: Seemahin Samay (1976), Dristibhangi O Jiban Darshan, Surjodoy (1982), Arakshita Swadhinatayi Paradhinata (1989), Bangladesh Nationalist Movement for Unity: A Historical Necessity. Died in Islamabad, Pakistan.  A. S. M. Abdur Rab ()

A. S. M. Abdur Rab ()  Hasanul Huq Inu ()

Hasanul Huq Inu ()  Mohammed Shahjahan ()

Mohammed Shahjahan ()  M. B. Manna ()

M. B. Manna ()  Anwar Hossain ()

Anwar Hossain ()  Ziauddin Ahmad ()

Ziauddin Ahmad ()  Serajul Alam Khan ()

Serajul Alam Khan ()  Akhlaqur Rahman ()

Akhlaqur Rahman ()  K. B. M. Mahmood ()

K. B. M. Mahmood ()  Saleha Begum ()

Saleha Begum ()  Peter Custers ()

Peter Custers ()

Solitary confinement in Rajshahi District Jail

Within two weeks of Colonel Taher's arrest, General Zia ordered that he be moved out of the capital and taken to Rajshahi, north-west of Bangladesh. It was considered too risky to transport Colonel Taher overland, thus on 6 December 1975, locked in handcuffs, he was flown by helicopter to Rajshahi District Jail where he'd spend the next six months in solitary confinement.

During this period Bangladesh Government was successful in suppressing many officers' uprising throughout the country. The two most notable were at Chittagong in March 1976 and Bogra a month later. The Bogra Mutiny, led by self-confessed Sheikh Mujibur Rahman killer Colonel Syed Farook Rahman, resulted in the disbanding of the Bengal Lancers.

With the restoration of discipline in the armed forces, General Zia was pressured from "hawkish" officers within the army and senior officials to act against the recalcitrant JSD leaders and their associates and 'settle the matter'. Amongst these were top officials of the National Security Intelligence (NSI), headed by A. M. S. Safdar, and the Home Ministry, headed by Salauddin Ahmed. Both A. M. S. Safdar and Salauddin Ahmed were the senior-most intelligence and internal security officials during the era of Ayub Khan and moved into their positions immediately following Sheikh Mujib's assassination.

Pressure began to build up among the councils at the top echelon of the officer corps for an act of revenge against Taher from which there could be no recall...and a glass of Black Label in the evening remained the touchstone of their military philosophy.

A number of these suddenly rehabilitated technocrats had during the 1971 been accused of active collaboration with the Pakistan Army.

It was this lobby which collectively pressed for a trial. Zia, recognising that his main rival for leadership in the armed forces had to be dealt with, moved with the wishes of the Islamic right and ordered a trial.

A. M. S. Safdar ()

A. M. S. Safdar ()  Salauddin Ahmed ()

Salauddin Ahmed ()

Repeal of 1972 Collaborators Act

On 24 January 1972, the new government of Bangladesh led by Sheikh Mujib had enacted a law called "Collaborators Act, 1972" to try the war criminals of Bangladesh Liberation War.

More than a hundred thousand persons were arrested under that Act. A total of 2,884 were brought to trial - of them, 752 were found guilty. The remaining 2,096 accused persons were found not guilty and freed.

In November 1973 the Government of Bangladesh declared a general amnesty. By virtue of the general amnesty, those accused or convicted for minor crimes under the Act were all set free. But those accused of rape, murder, arson or plunder were not pardoned. In other words, the general amnesty kept the scope of prosecution and trial of those accused of such serious crimes under the Act.

After the amnesty, the Act remained in force for a little over two years. In that period, no case was filed for the said four serious offences. Perhaps with this in mind the Act was repealed on 31 December 1975 by a Presidential Order. Nevertheless, the decision to repeal the Act proved unpopular with the masses who viewed the repulsion as an act of 'forgiveness' for the murderers who massacred 3 million Bengalis and feared the inclusion of all pro-Pakistan elements to take part in politics in independent Bangladesh.

In December 1975, the regime repealed the Collaborators Act of 1972, thus making the way clear for a return to politics of elements who had directly collaborated with the Pakistan occupation army in 1971.

Syed Badrul Ahsan, Journalist

Colonel Taher brought back to Dhaka Central Jail

On 22 May 1976 Colonel Taher was flown by helicopter and returned back to Dhaka where he was placed once again in solitary confinement in Dhaka Central Jail under tight security. Colonel Taher, along with the rest of the accused were denied access to legal counsel and communication with relatives throughout the period of detention, despite repeated requests. No newspapers reported on the dramatic event that was about to unfold.

Special Military Tribunal formed for secret trial

On 15 June 1976 an announcement was made that a Special Military Tribunal, designated 'No. 1', had been formed. It was to be chaired by a full army colonel, Yusuf Haider, a conservative repatriate who had not fought in 1971. The Tribunal contained four other judges: Mohammad Abdul Rashid (then Wing Commander from the Air Force), Siddique Ahmed (Acting Commander from the Navy), Mohd Abdul Ali (first-class magistrate of Sadar South, Dhaka), and Hasan Morshed (first-class magistrate of Sadar North, Dhaka).

Six days later, on 21 June 1976, the tribunal convened and opened the secret trial of Colonel Taher and the other accused inside Dhaka Central Jail. Hearings of the trial began in front of camera under strict security and media control and under rules which do not comply with the ordinary provisions laid down in the Procedural Code. The defence team was led by Ataur Rahman whilst prosecution was led by A. T. M. Afzal. The lawyers had to operate under an oath of secrecy (and still are) not to disclose anything learned in the course of or in connection with the trial proceedings.

Yusuf Haider ()

Yusuf Haider ()  Mohammad Abdul Rashid ()

Mohammad Abdul Rashid ()  Siddique Ahmed ()

Siddique Ahmed ()  Mohd. Abdul Ali ()

Mohd. Abdul Ali ()  Hasan Morshed ()

Hasan Morshed ()  Ataur Rahman ()

Ataur Rahman ()  A. T. M. Afzal ()

A. T. M. Afzal ()

The trial opened on 21 June 1976 behind the tall yellow-stained walls of Dhaka Central Jail. Never before in the history of either Bangladesh or 'East Pakistan' had a trial been held within the confines of any jail. A complete news blackout on the case was imposed inside the country and lawyers defending the accused had to take an oath of secrecy regarding the proceedings. Security at the prison was exceptional: sand-bagged machine gun nests circled every entrance. It was assumed the authorities were convening the tribunal within the jail to avoid the possibility of trouble occurring en route to the courthouse.

On 28 June 1976, when the trial reopened, this correspondent, who had reported from Bangladesh for a full year in 1974, stood outside the gates of Dhaka Central Jail taking photographs of the Chief Prosecutor, A. T. M. Afzal, the Chairman of the Tribunal, Colonel Yusuf Haider and others as they entered the prison gates. I was told by police officers present that the trial was top secret and I was not allowed to photograph anyone or anything. I said I had been reporting on Bangladesh for several years. I was a relatively well informed person and I was unaware of any such official guidelines or orders. If they wished me to stop photographing or reporting the case, I suggested they should show me a written order from the Information Ministry to that effect. Otherwise, I would continue my work as a journalist without interruption. I then raised my camera and photographed the police officer who was questioning me. He threw up his hands to cover his face and ran away.

There were many ironies that morning when the heavy iron gates at Dhaka's Central Jail swung open and snapped closed admitting 30 black-coated barristers into the opening session. The trial and the charge of armed rebellion against established authority occurred at a time when there had been four governments in the past year, each succeeding the other by force of arms. Moreover, those officers who were part of Khaled Musharraf's 3 November 1975 coup d'etat and who were dubbed at the time by the official press as 'Indian agents', had all been released from detention. Most notable among these was Brigadier Shafaat Jamil who had placed Ziaur Rahman under house arrest during the four days they had taken power. So it was that those officers who were behind the 3 November 1975 anti-Zia coup were freed, and those men who staged a general uprising which freed Zia, now went on trial for their lives.

On 28 June 1976 the trial reopened. Colonel Taher initially refused to attend the tribunal calling it "an instrument of the government to commit crimes in the name of justice".

The ordinance promulgated on 15 June 1976 is a black law. It was promulgated merely to suit the designs of the government. The ordinance is illegal. So, this tribunal ceases to have any right legally or morally to try me. The act of this Tribunal has put to shame what good things human civilisation achieved through constant endeavour from the beginning of time until today.

According to Amnesty, as of 21 June 1976, when the trial started, none of the accused had been able to meet his lawyer.

...Amnesty concludes its report summarising allegations of post-arrest treatment of prisoners. It reviews accusations of beatings and the use of burning cigarettes during periods of interrogation, particularly those which occur at National Security Intelligence (NSI) interrogation centres and in Dhaka Cantonment. It mentions specifically the JSD leader, Sirajul Alam Khan, who "according to reliable reports, during his prolonged interrogation had been deprived of food, drink, and sleep".

Colonel Taher also said that if he were to be judged, the panel must be made up of Mukti Bahini officers from the Army, who had fought for the independence of the country, and not by men like Yusuf Haider who had taken no part in the Liberation War. But when the tribunal was formed no Mukti Bahini officer would sit on it. Eventually Colonel Taher was persuaded by his lawyers to participate in the trial.

Taher's lawyers were finally able to persuade him to participate in the trial. They believed at first the tribunal would be able to function without intimidation. It is a decision many of them regretted later, when it became known that Taher's sentence had been decided even before the tribunal opened.

The case went on for 17 more days.

...In conclusion, Mr Chairman, I will only say that I love my country and my people. I am part of the soul of this nation. I ask if you be part of the same soul that you protect it as if it were your own. And I warn the corrupt gentry of the country, do not dare my life. If you do, you will burn the soul of this nation.

Victory to the revolution!

Victory to my people!

Long live Bangladesh!

Life sentence for Colonel Taher and heavy punishment for other JSD members

On 17 July 1976 at 3 O'clock the verdict was delivered. Chairman of the Tribunal, Yusuf Haider, announced Colonel Taher was guilty of treason and 'propagating political opinion' among service personnel, and sentenced him to death. Colonel Taher was to hang. Sixteen others were sentenced to different terms of imprisonment. Amongst these were Colonel Taher's brother Abu Yusuf Khan and Major M. A. Jalil who were both sentenced to life imprisonment and all their property would be confiscated. Another brother, Prof. Anwar Hossain, and fellow members Hasanul Haque Inu, ASM Abdur Rab, and Major Ziauddin were given 10 years rigorous imprisonment and a penalty each of 10,000 takas each. Saleha Begum and Rabiul Alam had been given 5 years imprisonment and penalty of 5,000 takas each.

The remaining sixteen, including Dr. Akhlaqur Rahman, K. B. M. Mahmood, and M. B. Manna were set free. Some of the accused were tried in absentia.

Sixteen accused awarded various prison term were:

- Major (retd) M. A. Jalil

- Major Abu Yusuf Khan

- Major Ziauddin Ahmad

- ASM Abdur Rab

- Prof. Anwar Hossain

- Hasanul Hoque Inu

- Serajul Alam Khan

- Altaf Hossain

- Shamsul Haque

- Nayek subedar Md Jalaluddin

- Havilder M. A. Barek

- Rabiul Alam

- Saleha Begum

- Nayek Siddiqur Rahman

- Havilder Abdul Hye Mazumder

- J. Majeed

The sixteen that were acquitted were:

- Dr. Akhlaqur Rahman

- Anwar Shidique

- Mohiuddin

- Nayek subedar Bazlur Rahman

- Mahbubur Rahman Manna

- Warasat Hossain Belal

- Md. Shahjahan

- K. B. M. Mahmood

- Sharif Nurul Ambia

- Havilder Sultan Ahmed

- Nayek A. Bari

- Sgt. Kazi A. Kader

- Kazi Rakunuddin

- Nayek subedar A. Latif Akhand

- Nayek Shamsuddin

- Sgt. Syed Rafiqul Islam

The adverse publicity in the West over the trials has stung the regime which clearly had not expected it. A senior officer snapped angrily to this correspondent: 'The Courts are too lenient and open to exploitation by these people'. But one man who attended the first trial claimed that most of the evidence presented was so thin and suspect that 'it would have been embarrassing to the regime if made public'.

Hearing the tribunal declare the death sentence Colonel Taher broke out into a tremendous laughter. He was taken to Cell Number 8 - the cell assigned to prisoners who are to be hanged. In the cells adjacent to him were three other prisoners (or 'victims' as Colonel Taher termed them) waiting for the gallows.

It is a small cell. Quite clean. It is all right.

The Chief Prosecutor, A. F. M. Afzal, after the trial would be rewarded with an appointment to the position of Judge of the Dhaka High Court. But Afzal, a worried man, would anxiously claim to his colleagues that he was more stunned than anyone with the sentence of death. As prosecutor, he claimed, he had never asked for death sentence. He said such a judgment was impossible. There was no law in existence under which Taher could be executed for the crimes with which he was charged.

But did Afzal publicly protest the verdict or express regret for the role he played in this tragic charade? Did he ever consider walking out and say he would not be a party to a secret trial held within the boundary of the central jail?

The next day, the government ordered newspapers to publish an official statement on the case and nothing more. Colonel Taher's death sentence was published on the front page with the main headline in the Bangladesh Observer reading 'Taher to die'. The morning papers mention that Colonel Taher led the Sepoy Revolution of 7 November 1975 but refrain from mentioning that Ziaur Rahman was released under his command.

It was the first news through the Bengali media that the country had of the case and it came at the end of the trial as a fait accompli.

Last testimony

On 18 July 1976, three days before he was hanged, Colonel Taher wrote a final letter from prison to his family.

Respected father, mother, my dearest Lutfa, bhaijan, my brothers and sisters,

...At the very last moment the tribunal proclaimed my death sentence; and in great haste they left the court like dogs in flight.

Among those convicted there was only a single lament: why had they not also been sentenced to death? Suddenly there were cries from all quarters of the jail-house. Defiant and ever louder: "Taher Bhai! Red Salute! Lal Salam!" Can these high walls hold back this cry? Will not the echoes of this call reach into the hearts of the people of my country?

Our lawyers were stunned at the announcement of the verdict. They came and told me that, although there is no appeal from this tribunal, they would issue a writ to the Supreme Court. The entire workings and procedure of the tribunal had been unconstitutional and illegal. They said that simultaneously they would issue an appeal to the President. Then I made it clear to them that no such appeal was to be issued. We had installed this President and I would not petition for my life from these traitors.

...They [i.e. rest of detainees] have left. All of them. Saleha and I come out together. She goes to her cell. As I pass, prisoners and political detainees peer out with eager eyes from behind the doors and windows of their locked cells. Matin Sahib, Tipu Biswas, and the others raise their hands in the sign of victory. This trial has united the revolutionaries almost without their knowledge.

When standing face-to-face with death, I turn to look back on my life and find nothing to be ashamed of. I see many events which unite me irrevocably to our people. Can I have a greater joy or happiness than this?

Nitu, Jishu, and Mishu...everyone comes crowding into my memory. I have not left behind any wealth or property for them, but our entire nation is there for their future. We have seen thousands of naked children deprived of love and affection. We wanted a home for them. Is this dawn too distant for the Bengali people? No, it is not too far off. The sun is about to rise.

I have given my blood for the creation of this country. And now I shall give my life. Let this illuminate and infuse new strength into the souls of our people. What greater reward could there be for me?

No one can kill me. I live in the midst of the masses. My pulse beats in their pulse. If I am to be killed, the entire people must also be killed. What force can do that? None.

...I do not fear death. Zia is a traitor and a conspirator and has had to take refuge in lies to discredit me before the people. Tell [lawyer] Ataur Rahman and the others that it is their moral responsibilities to expose the truth - and if they fail in this duty history will not forgive them.

My greatest respect, my love, and my everlasting affection be with you all.

- Taher

Extract from Colonel Abu Taher's final letter sent from Dhaka Central Jail on 18 July 1976

The family met Colonel Taher for the last time in the afternoon of 19 July 1975.

He [Taher] was completely natural and cheerful. He read to us what he had written after the tribunal gave the verdict. To me he said, "It does not befit you to feel sad. After Khudiram I will be the first in South Asia to die like this". When I told him others had asked me to file a mercy petition, he said, "Is that to bring me the illusion of life? Is my life smaller than the life of Sayem and Zia?"

He gave us so much courage that we came out laughing as well.

President Sayem turns down clemency petition

During those days in Bangladesh there was no provision in law for appeal to any legal authority. Therefore, Colonel Taher's lawyers made an appeal for clemency to President Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem. But the President, a former Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, turned it down.

Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem ()

Abu Sadat Mohammad Sayem ()

Five years earlier, he [Sayem] had written the most significant legal decision on capital punishment and the rights of an accused ever to be handed down by the Supreme Court. In the case against Purna Chandra Mondal, Sayem threw out a death sentence passed on the accused. The judgement established a legal precedent as significant as the Miranda decision in the United States. Sayem argued that "the last moment appointment of a defence lawyer for an accused virtually negated the right of the accused to be properly defended in the case".

Colonel Taher was not allowed access to a lawyer until the day the case against him opened. Nevertheless, A. M. Sayem, who as a judge had written that no man under law could be sentenced to death were he not given the right of an adequate defence, now in the position of President of the country, reaffirmed the death sentence on Colonel Taher. And he made his decision within 24-hours of the sentencing.

Amnesty International appeals for re-trial

In London Amnesty International's Headquarters issued an urgent appeal to the Bangladesh President to grant Colonel Taher clemency.

Amnesty International ()

Amnesty International ()

A martial law trial held in camera inside jail fails short of internationally accepted standards as laid down in the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights. Before criminal courts the case against the accused can be established according to the normal process of law and with all legal safeguards, including the right of appeal to the highest judicial authorities.

Amnesty International is disturbed that it cannot verify most serious reports received by the delegates during their visit that convictions of the accused were reached solely on the basis of evidence given by 7 co-defendents who had turned state witnesses. According to these reports, this evidence was used in a way not in compliance with the ordinary rules laid down in the Code of Criminal Procedure. If these reports are correct, the accused could never have been convicted if their trial had taken place before an ordinary criminal court.

Under these circumstances, Amnesty International has to conclude that the trial fell far short of international standards and consequently finds it impossible to accept the findings of the court.

The Amnesty appeal went out to President Sayem on 20 July 1976. The next morning Colonel Taher was executed.

First political execution in independent Bangladesh

On Wednesday 21 July 1976, four days after the military court order, at 4 am Lieutenant Colonel Abu Taher was hanged in Dhaka Central Jail. He was only 37 years old.

A former hero of the independence war, Colonel Taher became Bangladesh's first official political execution since independence and the first in Bengal since the days of British colonial rule. After Khudiram's hanging in 1908, it was another 26 years until the British would repeat a political execution in the volatile atmosphere of Bengal. In 1934, Surja Sen, the organiser of the famous Chittagong Armoury Raid, was sentenced and hanged. In the 42 years that passed there was never another political execution in Bengal.

This does not mean there were not countless, political murders and massacres.

Throughout this period of history, as state power moved from the British into the hands of bourgeois nationalist regimes in India and Pakistan, and then in 1971 onto Bangladesh, at least in Bengal no prisoner was ever executed for being a revolutionary. Thousands rotted in prison then, as they do today. But the stigma of the death sentence passed by an official court still smelled colonial, and the memory of Khudiram and Surja Sen tempered the gallows instincts of the new authorities.

Ten days after Colonel Taher was dead the Bangladesh Law Ministry remedied the 'legal' discrepancy which prevented political execution. On 31 July 1976 the ministry published the Martial Law Decree's 20th Amendment which made it a crime "punishable with death" for anyone who "propagates any political opinion" among the armed forces of Bangladesh.

Colonel Taher's execution became the first round of death under Ziaur Rahman's regime and a prelude to the mass executions that were to follow.

Soon afterward, in another secret trial on 21 September 1976, Dutch journalist Peter Custers and six JSD leaders were sentenced to 14 years imprisonment. But Peter appealed to the President for mercy and this time A. M. Sayem did grant the wish. Peter Custers was pardoned and deported back to his home country of Holland immediately.

The death of Colonel Abu Taher in such 'dark circumstances', less than a year after he had helped Ziaur Rahman triumph over Major Khaled Musharraf and arguably save his life in the process, and the repulsion of the 1972 Collaborators Act - both carried out under CMLA Justice Sayem - would provide ammunition for future Zia assassins as he was perceived as the 'real' person behind these acts.

For the soldiers who had experienced the Liberation war and 7th November 'revolution', Colonel Taher’s arrest, followed by his death sentence, was an act of treason. This triggered a series of unprecedented rebellions.

Taher indeed became potentially more threatening, post-mortem, to Zia.

Jérémie Codron, Analyst