Abortive coup of September and October 1977 shakes Zia regime

By far the most dramatic political event of 1977 was the abortive coup on 30 September 1977 and 2 October 1977 which killed 11 air force officers and 10 soldiers.

Bogra mutiny - Zia's hometown becomes citadel of anti-Zia activities

On 30 September 1977, while the attention of the government was riveted on the Japanese hijacking event, an unrelated but significant mutiny broke out in Bogra, hometown of Ziaur Rahman. The army officers of 22nd Bengal Regiment attempted to seize the local air force base in order to negotiate the freedom of Lt. Col. Syed Farook Rahman. The Bogra Mutiny resulted in the death of 10 soldiers including Lieutenant Hassan. Though the mutiny was quickly quelled on the night of 2 October 1977, a second mutiny occurred in Dhaka which coincided with the Japanese hijacking.

Indeed, just before the non-commissioned officers and men of the air force tried to seize power on 2 October 1977 the class conflict in the army heightened when the slain officers from Bogra were brought to Dhaka Cantonment for burial. The father of one of the dead charged in his eulogy that the army had fallen so low that it failed to protect its own officers against undisciplined and murderous soldiers. Brigadier M. A. Manzoor, who was then the chief of the General Staff of the army, responded that the whole Bangladesh army could not be held responsible for the misdeeds of a few soldiers, and that soldiers needed their officers for leadership. This rejoinder apparently satisfied both the parents of the dead officers and the soldiers. But for the swift rejoinder, there might have been an uprising of soldiers then and there, Manzoor's actions only delayed another attempt by the soldiers to take over the reins of government.

Mutiny spreads to Dhaka

On 1 October 1977, at midnight, a number of non-commissioned air force officers and airmen attempted a coup against senior air force officers and the Zia regime. The coup involved a group of non-commissioned officers (NCOs), junior commissioned officers (JCOs), and soldiers from the army.

The JAL hijacking was a perfect distraction for these rebel officers. The opportunity to attack on 28th September - celebrated as 'Air Force Day' in Bangladesh - was lost not only by the suddenness of the hijacking but also because President Zia had informed Air Vice Marshall Mahmud that he was unable to be part of the celebrations. Apparently, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat meet President Zia in Cairo few days before 28 September 1977 and warned him of a plot to assassinate him over the next few days. Ziaur Rahman took the hint seriously.

The rebel officers attacked the President's house and took over the Dhaka radio station very briefly. They announced that a revolution of the workers, peasants, students, and people's army was underway and declared their coup a success.

Meanwhile, another rebel group attempted to take over Dhaka airport control tower where Air Vice Marshal A. G. Mahmud and other senior officers of the government were engaged in negotiations with the Japanese hijackers. Here the sepoy mutiny takes a savage turn. They wanted to paralyse the Bangladesh military by killing all the senior air force officers. This explains the riddle behind Air Marshal Mahmud's "if I tell you these people are not mine you can kill them" remark. He was in fact ordering his officers regarding the Bengali mutineers and not the JRA.

We hear Mahmud imploring Dankesu to shoot and kill the mutineers; Dankesu replies mechanically, with a euphemism that smacks of the strategic language of international diplomacy: "I have understood that you have internal problems". And the hostages inadvertently witness and photograph the drama from inside the aircraft.

The fighting continued and the mutineers captured a number of air force officers and executed 11 of them by firing squad. Beside Ansar Chowdhury, these included Wing Commander Anwar Ali Shaikh, Squadron Leader Md. Abdul Matin, and Group Captain Raas Masud, who was also the husband of Vice Marshal A. G. Mahmud's sister. The vice marshal himself and a number of high officials escaped unhurt and after a day of intense battle, Vice Marshal Mahmud, Air Commodore Wahidullah and Group Captain Saiful Azam were finally able to disarm the mutineers on 3 October 1977.

My family thought I had not done enough to save my brother-in-law. This created tension and unhappiness within my family, which lasts till today.

A. G. Mahmud on the tragic loss of his colleague and brother-in-law Raas Masud

Ansar Chowdhury ()

Ansar Chowdhury ()  Anwar Ali Shaikh ()

Anwar Ali Shaikh ()  Md. Abdul Matin ()

Md. Abdul Matin ()  Raas Masud ()

Raas Masud ()  Wahidullah ()

Wahidullah ()  Saiful Azam ()

Saiful Azam ()

A large part of this disarmament was also down to the sharp thinking and foresight of General Abul Manzoor. Possibly suspecting another coup attempt by the non-commissioned officers and jawans, and also because of his deep loyalty to President Ziaur Rahman, General Manzoor ordered the 46th Infantry Brigade, known as the Dhaka Brigade and commanded by Lieutenant Colonel M. Ameen, to report directly to the president and bypass the 9th Division commanded by Major General Mir Shawkat Ali in case of any unrest among the rank and file.

This move proved to be a lifesaver. Since the brigade was alert and close to the action they were quick to come to the rescue of the President when the rebels tried to overpower the presidential guards and completely overrun the defence perimeters of the president's house. Meanwhile the 9th Division was based outside the capital in Savar and, despite the early warnings, failed to act in time. They came to support the 46th Brigade early in the morning (of 2 October 1977) and put an end to the rebellion.

Muhammad Abul Manzoor (24 January 1940 - April 1981) Bir Uttam. Sector 8 (Jessore) Commander from September 1971 - December 1971 during Mukhtijuddho. Born in village of Gopinathpur, Kasba thana, Comilla district to a relatively poor family originally from village Kamalpur in Chatkhil thana of Noakhali district. Passed senior Cambridge (1955) and ISc examination (Intermediate degree) from the Air Force Cadet College at Sarghoda, West Pakistan (1956) and attended Dhaka University for a year before joining the military. Distinguished himself as a brilliant student at the Pakistan Military Academy, obtaining his PSC degree from Defence Service Staff College in Canada (1958) and joined, subsequently built a reputation as a bright and able officer. Escaped in July 1971 from Sialkot, Pakistan to Bangladesh to fight in Muktijuddho. After independence appointed Brigade Commander of 55 Brigade in Jessore. Joined Bangladesh High Commission in New Delhi, India, as military adviser (1973 - 1975). Chief of General Staff of Bangladesh Army (13 November 1975), GOC of 24th Division of Bangladesh army in Chittagong (1977 - 1981). Promoted to Colonel (1975), Brigadier (1977) and finally to Major General (1980) - and at 41-years-old became one of the youngest generals of a front-line force in south-east Asia's history. Declared himself as Supreme Commander of the armed forces and Chief of civil administration after assassination of President Ziaur Rahman on 30 May 1981. Captured and killed in mysterious circumstances three days later on 2 June 1981 after trying to flee.

Muhammad Abul Manzoor (24 January 1940 - April 1981) Bir Uttam. Sector 8 (Jessore) Commander from September 1971 - December 1971 during Mukhtijuddho. Born in village of Gopinathpur, Kasba thana, Comilla district to a relatively poor family originally from village Kamalpur in Chatkhil thana of Noakhali district. Passed senior Cambridge (1955) and ISc examination (Intermediate degree) from the Air Force Cadet College at Sarghoda, West Pakistan (1956) and attended Dhaka University for a year before joining the military. Distinguished himself as a brilliant student at the Pakistan Military Academy, obtaining his PSC degree from Defence Service Staff College in Canada (1958) and joined, subsequently built a reputation as a bright and able officer. Escaped in July 1971 from Sialkot, Pakistan to Bangladesh to fight in Muktijuddho. After independence appointed Brigade Commander of 55 Brigade in Jessore. Joined Bangladesh High Commission in New Delhi, India, as military adviser (1973 - 1975). Chief of General Staff of Bangladesh Army (13 November 1975), GOC of 24th Division of Bangladesh army in Chittagong (1977 - 1981). Promoted to Colonel (1975), Brigadier (1977) and finally to Major General (1980) - and at 41-years-old became one of the youngest generals of a front-line force in south-east Asia's history. Declared himself as Supreme Commander of the armed forces and Chief of civil administration after assassination of President Ziaur Rahman on 30 May 1981. Captured and killed in mysterious circumstances three days later on 2 June 1981 after trying to flee. M. Ameen ()

M. Ameen ()

This move by Manzoor, and the inability of the mutineers to generate widespread support from soldiers and airmen, saved Zia in October when some non-commissioned air force personnel led a soldiers' coup against the Zia regime.

The [46th] brigade's timely action, especially the courageous stand by Lt. Col. M. Ameen and his fellow officers and loyal soldiers, averted what could have the end of Zia as well as his government.

Had the final thrust by the airmen and soldiers against the president's house succeeded, fence sitters within the army air force would probably have joined the rebels. But when the rebels were defeated in the final encounter near the president's house, the attempted coup d'etat failed and what could have been a general uprising of the mass of soldiers turned into a localised mutiny of the disappointed, frustrated, and revengeful non-officer class of the air force and army.

The aborted coup attempt of 2 October 1977 was undoubtedly the most serious of them. First, it occurred in the capital, Dhaka, whereas the other mutinies generally took place in peripheral units. Second, this coordinated operation of soldiers, NCOs and JCOs belonging to the army and the air force, clearly aimed at assassinating Zia and creating a soldiers’ revolutionary committee on the same pattern as the November 1975 sepoy biplob. But the most immediate incentive for this revolt was the avenging of Colonel Taher's death, now raised by his men to the status of a martyred 'Liberation hero'. The coup, whose effects would last until January 1978, failed because of the loyalty of several top-ranking officers, like the Chief of General Staff of the Armed Forces Division, Major-General Abul Manzoor, an ex-freedom fighter who had fought with Zia in 1971, and the commander of the Dhaka brigade, Lieutenant-Colonel Ameen.

There are basically two interpretations of the 2 October 1977 attempted coup and massacre of air force officers: one view, subscribed to by a few senior Bangladesh army officers, suggest that the attempted coup by the air force NCOs and JCOs was carefully synchronised with the hijacking of the Japan Airlines plane. In collaborating with the Japanese Red Army radicals, and possibly supported by the Soviet Union, the Bangladesh air force sought to change the government in favour of a pro-Soviet regime. In support of this point of view, these senior officers (which includes Brigadier Sabehuddin, formerly Deputy Director of Jatiyo Rakkhi Bahini) have pointed out that the negotiations were intentionally made unusually long, and despite the availability of commandos who could have overpowered the hijackers, the negotiators opted for a slow process of delivering the $6 million ransom to the hijackers, the sixth phase of delivery taking an abnormally long time. The whole hijacking episode, in short, according to these officers, was designed as a diversion to allow the coup leaders sufficient time to successfully bring about the fall of the Zia government in an emergency situation.

Another view held by a few junior officers and a very important senior officer maintains that the hijacking incident actually saved Zia and his regime. According to this view, the JSD cells, after testing the determination and will of the officer and loyal soldiers through sporadic revolts of soldiers in different parts of Bangladesh, came up with a master plan for the takeover of the government by killing the high officials of the army and the government at the Air Force day reception on 9 October 1977. Their plan was totally upset by the hijacking, which caused the cancellation of the grand reception. The ringleaders could not take a chance on postponing the coup, so they struck a few days sooner, thinking that they might succeed in the melee.

The abortive October coup was no surprise to observers in Bangladesh. A politicised army like that of Bangladesh is susceptible to coups and counter coups. The liberation legacy and the upheavels of 1975 left the marks of disunity among the soldiers. Hard core followers of JSD and the Marxists were known to be working among the rank and file. Whenever there is an insurrection in Bangladesh, a number of officers are killed by the Jawans (soldiers). Leftist elements have sought to radicalise the soldiers, but personal vendettas are also at work.

Execution of rebel officers

The army quickly put down the rebellion, but the government was severely shaken.

After the 2 October 1977 military uprising in Dhaka, Zia appeared on Bangladesh television visibly shaken. It is said in Dhaka that fighting reached his own quarters the night of the rebellion and that he barely escaped. What followed was the mass wave of executions of all presumed and actual enemies. Politically Zia was tottering. A fresh infusion of support and a clearer sense of direction was needed if he had to survive.

It was not clear who were the actual leaders of the attempted insurrection, though the rhetoric of the mutineer's radio announcement hinted that radicals were behind the uprising. President Zia went on radio to announce that all those involved in the coup will be tried and severely punished. Initially, the Dhaka authorities played down the incident without blaming any political group for the uprising. However, a few days later, they banned the JSD, pro-Moscow Communist Party, and Democratic League for having incited the coup. Three leaders of these parties were also arrested.

As a result of the coup attempt a large number of military personnel were executed. It is believed that General Zia was under pressure from his colleagues, who fear that such coup attempts might become a periodic feature in Bangladesh, threatening the stability of the country unless drastic steps are taken to depoliticise the soldiers.

This explains why the military tribunals quickly went into action immediately after the abortive coup. Observers in Dhaka feel that Zia was under strong pressure to take such drastic action.

While only 11 died on the tarmac, countless number of suspected plotters, mostly air force officers, were rounded up afterwards and summarily tried and executed. Though it may never be possible to know the exact number, total casualties on both sides is believed to have exceeded 230, according to unconfirmed sources. This had far-reaching implications for Bangladeshi politics and history. Bangladesh Air Force took a long time to recover and subsequent to these purges, but also in alignment with the national strategic vision, the army still towers over the other two corps to this day.

The facts...are set off in an eerie pattern from the moment Zia loyalists, Mir Shawkat Ali for instance, move resolutely against the mutineers. Over the next twenty days or so, it would be an operation of relentless cruelty as the Zia regime, guided by vindictiveness and palpably oblivious to all norms of civilised behaviour, rounded up hundreds of innocent air force men and inaugurated what would eventually turn into a story of unimaginable horror. Kangaroo courts, officially described as military tribunals, swiftly handed down verdicts of guilty on those taken into custody; and night after night, inside the grim premises of the central jail in the capital, the bodies of hanged men dropped into pits for hours on end. It was Azimpur graveyard [in Dhaka] which, throughout October 1977, saw brisk nocturnal activity as the dead men were hastily buried, unbeknownst to their families.

There are other accounts, from men who were among the lucky few to escape the noose but nevertheless found themselves condemned to varied terms of imprisonment. The strand of thought throughout the stories runs along similar patterns.

Syed Badrul Ahsan, Journalist

Surprisingly, public life in Dhaka was not seriously affected by the upheavals in the military. The rebels were wiped out by dawn and the streets were open to the public except for a few restricted areas. Obviously, tension and a sense of insecurity prevailed, but this proved to be a serious problem more amongst the military then the civilian. Nevertheless, the authorities feared that people were slowly becoming sensitive to military indiscipline, especially post the turbulence of 1975, and this could "snowball into a growing sentiment" against continued martial law. Political leaders who wanted the military out of politics used the opportunity to argue for an early election in the hope of transferring power back to them.

International condemnation of execution

The revolts, which attracted worldwide coverage, were dismissed by the government as a conflict between air force enlisted men and officers regarding pay and service conditions. But the execution of rebel officers received international condemnation.

The relationship between Bangladesh and India also soured after the abortive coup. On 15 October 1977 Zia strongly condemned the mutinous acts at Bogra and Dhaka and blamed the conspirators for trying to make Bangladesh a "satellite". The Government of Bangladesh blamed "foreign powers" for the attempted coup and though they stopped short of naming these 'powers', they implied both India and Soviet Union were behind the rebels. Indian unhappiness was clear when the government expressed dissatisfaction over "attempts by Dhaka to drag Delhi's name into the recent military uprisings in Bogra and Dhaka". Jaya Prakash Narayan, the prominent Indian leader, openly criticised Bangladesh for executing the alleged conspirators and large scale arrests of political dissidents. The Soviet Union and Amnesty International also criticised Bangladesh for the trial and execution of the alleged conspirators. Amnesty International also protested the summary executions.

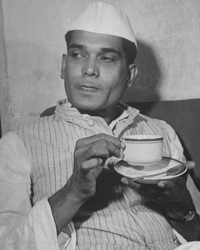

Jaya Prakash Narayan ()

Jaya Prakash Narayan ()

Following the death of his colleagues in front of his eyes and the subsequent trials of air force men before martial law tribunals, Air Vice Marshall Mahmud decided to opt out of the force as he felt his command over his own force had weakened. He also declined Ziaur Rahman's offer to join his political party. However, later, he joined the cabinet of Bangladesh's second military ruler, General Ershad, after he requested Mahmud' services in tackling a probable food crisis.

Within a month of the Bogra-Dhaka revolts it was announced that Ziaur Rahman would form his own political party. Zia also inducted 6 new advisers into his cabinet with a view to having a positive and crucial impact on his political future.

The abortive coup had shaken the stability that Zia provided the country since November 1975 and on which he based most of his claim to legitimacy. The internal politics of Bangladesh has also been internationalised as a result of foreign criticism of the tough measures taken against those who were allegedly involved in the insurrection. There are signs of public uneasiness about military indiscipline and Zia will have to put a lid on the soldiers' scramble for power. The military authorities in Dhaka will have to review their political strategy in the light of what happened in the fall. How Zia will depoliticise a deeply politicised military is not yet clear.

Two main options seems to be available for the Dhaka generals: they may bow out of politics and transfer the power to elected representatives and concentrate on building a genuinely professional military which would not meddle into politics. Or the military may continue to play a political role indefinitely, oscillating between an authoritarian system and some of kind of "controlled democracy".