'Civilianisation' of Ziaur Rahman

Referendum: Zia's quest for political legitimacy

On 19 November 1976 Ziaur Rahman once again became the Chief Martial Law Administrator (after his first spell on 7 November 1975 lasting few hours) by replacing Justice Sayem who had been elevated to President. However, after President Sayem resigned on 21 April 1977 on the grounds of ill health, Ziaur Rahman became the 7th President of Bangladesh and still retained his position as CMLA and Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces.

In his first broadcast to the nation on 11 November 1975 Ziaur Rahman claimed that he was a "soldier", not a politician. But once General Zia formally assumed the presidency in April 1977 he took a number of steps to legitimise his regime. These included a presidential referendum, presidential election, the formation of a political party, parliamentary elections, and the creation of new village institutions.

Every military regime usually claims that it will restore democracy and hand power to the civilians as soon as law and order is restored. But what often happens afterwards is that it tries to remain in power through a continuous process of civilianisation and legitimisation. The military regime of General Ziaur Rahman was no exception to this pattern.

...During the Zia period the state apparatus in Bangladesh was dominated by civil-military bureaucrats. The Zia regime was fundamentally a resurrection of the "administrative state" under Ayub Khan in Pakistan. As [author Robert S.] Anderson points out, "there was a striking resemblance between Bangladesh after the 1975 coups and East Pakistan before its collapse in 1971. A similar marriage of convenience existed between the military and the civil service". And like their forebears in the administrative state of Pakistan, the civil-military bureaucrats in Bangladesh as an exclusive administrative group had been deeply imbued with a "guardianship" orientation. The broad administrative framework in which they worked did not undergo any fundamental change in Bangladesh. Like Bhutto's regime in Pakistan, Mujib's regime in Bangladesh was a short interlude in the persisting pattern of the administrative state.

In an address to the nation over the Bangladesh Radio and Television on 22 April 1977 President Zia proclaimed that general elections on the basis of universal adult franchise would be held in December 1978 to elect the members of Parliament.

I and my government believe in full democracy and are determined to restore the government of the elected representatives of the people in due time.

But for the time being, Zia announced, he would remain President and seek people's consent to continue as President through a referendum. Meanwhile, Zia issued a broad election manifesto, the 19-point program, which promised, in part, the promotion of the private sector, self-sufficiency in food production, population control, and agricultural development. In the national referendum held on 30 May 1977, few weeks into his presidency, President Zia turned to the people of Bangladesh for a vote of confidence and received an overwhelming 98.89% of the vote among the 85% voter turnout. The result was a great confidence booster for Ziaur Rahman and gave him a strong indication of his authority in Bangladesh. Although there was no serious challenge to the validity of the referendum, the critics were obviously suspicious of a such a massive victory with very few negative votes. For them it was reminiscent of similar experiments in third world nations giving their dictators close to a 100% endorsement of their policies.

Zia's landslide victory in presidential election over his Liberation War superior

Meanwhile, the October 1977 Dhaka mutiny had a profound effect on President Zia. Though unsuccessful, the coup was bloody and ideologically explosive enough to force Ziaur Rahman to ensure his legitmacy by holding a presidential election. Thus in April 1978 President Zia announced that there would be an election for the presidency in two months time, and restrictions on political parties were lifted as of May 1978. There were probably equally important reasons for Ziaur Rahman to hold the elections, such as keeping his electoral commitment to the people and maintaining his image as a trustworthy third world leader before the leadership of western democracies.

I was the PS (personal secretary) to the then deputy chief of the army Ziaur Rahman for two years. One day he gave me a form and said it was sent from BKSAL headquarters. Then he threw the form into a waste basket in front of me, let alone joining the party. [Zia took opinions of his personal staff before taking any decision, the senior BNP leader said] I gave a negative opinion about joining BKSAL when he sought mine. I had said the people of Bangladesh favour democracy. Sir (Zia), it won't be right to join BKSAL. Then he said the army should not be linked with politics and threw the form into the waste paper basket.

I was Zia's PS for one year after the incident.

Major M. Hafizuddin Ahmed, former personal secretary to Ziaur Rahman

Prior to the election, various political parties and groups aligned themselves into two distinct fronts - the Jatiyotabadi Front (JF, Nationalist Front) and Gonotantrik Oikyo Jote (GOJ, Democratic United Front). The JF nominated Ziaur Rahman and GOJ nominated General M. A. G. Osmani - Zia's Commander-in-Chief during Swadhinata Juddho and former Cabinet Minister of Sheikh Mujib - as the presidential candidates.

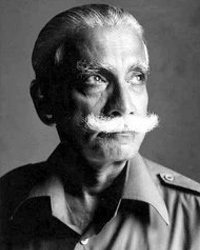

Muhammad Ataul Ghani (MAG) Osmani ()

Muhammad Ataul Ghani (MAG) Osmani ()

When the election was held as scheduled on 3 June 1978 Ziaur Rahman consolidated his power by winning a landslide victory. Zia beat his former chief by securing 76% of the total votes cast among the 54% voter turnout. General Osmani, on the other hand, received 21% of the votes cast. And despite the fact that the election was based on universal adult franchise and was considered more or less fair, 9 rival candidates, including General Osmani, bitterly complained about the time limitations - they were allowed to start campaigning only 20 days before the election - and Zia's unlimited use of governmental machinery for campaigning.

Nevertheless Zia was elected president for 5 years, proving his legitimate authority to rule.

Through his election for a five-year term, Zia had transformed himself from a "soldier" into a "politician".

Now fulfilling the triple role of President, CMLA, and Chief of Army Staff, Ziaur Rahman formed his own political party.

BNP - Zia's attempt to build a political base independent of the military?

Although General Zia had been elected President, he still did not have a mass political organisation of his own, and he moved steadily forward to build a political base for his regime. However, he was still undecided about a possible political front - whether to join an existing political party or to organise his own political party. In order to ensure support by all groups, President Zia initially adopted the tactic of not being identified with any political party. However, on 1 September 1978 - just few months before the 1979 parliamentary elections - President Zia launched a new political party, the Bangladesh Jatiyatabadi Dol or the Bangladesh Nationalist Party, popularly shortened to its accronym BNP. The BNP's 'open to all' philosophy attracted the Jatiyotabadi Gonotantrik Dal (JAGODAL), NAP(Bhashani), United People's Party (UPP), and the Muslim League who all joined the party. The BNP manifesto advocated a presidential form of government and set out 17 goals and objectives, including establishment of "people's democracy", "greater concentration on the private sector", "productivity oriented politics", "social and economic justice", and "multiple political parties".

Continual dissension within the army convinced Zia that he needed a powerful civilian political base if he were to govern effectively. But, perhaps more important, he began to enjoy immensely the give-and-take of Bangladesh politics once he decided to become a civilian leader.

In November 1978 President Zia redeemed his pledge for parliamentary elections by announcing that such elections would be held two months later on the basis of adult franchise. As scheduled, the election was held in February 1979 and was contested by 31 political parties. The results of the elections were a virtual endorsement of Zia's regime, with his BNP winning 206 of the 300 seats (i.e. over 66%) in the legislature.

The massive victory by the BNP underlined the continued confidence of the public in the leadership of President Zia, the soldier turned politician.

Council of Advisers & Council of Ministers

Initially, the core of the new state consisted of a Council of Advisers, which included, apart from 7 civilians, the 3 chiefs of the armed forces: General Ziaur Rahman (Chief of Army Staff), M. H. Khan (Naval Chief who had served in the Pakistan Navy for 20 years) and M. G. Tawab (Air Force Chief who had served in the Pakistan Air Force).

Of the 7 civilians, one was a former professor of Economics of Dhaka University and former Minister of Finance in the government of East Pakistan (1965-69), and the other six had bureaucratic background. The number of advisers was subsequently raised to 24, of whom 10 were from the Civil Service of Pakistan (CSP), 3 were military officers, and the rest technocrats.

Power still remained in the hands of Ziaur Rahman. Even though its members were elected, the parliament was not a sovereign body since it was subordinate and subservient to the President who was a military bureaucrat. The President was above parliament. In fact, the Parliament itself had been elected under terms and conditions set by the President, and could be summoned, prorogued, and dissolved by him at will. After the parliamentary elections in February 1979, President Ziaur Rahman formed a Council of Ministers, whose members were appointed by the President and held office at his pleasure.

Earlier, in December 1978, Zia had decreed an amendment to the Constitution, providing that:

- the President could appoint one-fifth of the membership of the Council of Ministers from among people who were not members of Parliament;

- the President had the right to withhold assent from any bill passed by parliament, which could be overridden only in a national referendum, and

- the President could enter into any treaties with foreign nations in the "national interest" without informing Parliament.

During the five and half years of Zia's rule, the civil-military bureaucrats were continuously dominant in the Council of Ministers and its predecessor body, the Council of Advisers. In 1981 there were 24 full ministers in the cabinet of whom 6 were military bureaucrats, 5 civil servants, 6 technocrats, 4 businessmen, one landlord, and 2 lawyers. In addition to the Council of Ministers, the President had his own secretariat consisting of three divisions - Personal (Mahbub Alam Chashi), General and Economic (S. A. Khair), and Information (A. H. K. Sadique) - all headed by civil bureaucrats. Apart from the national level, the state made an effort to strengthen the position of civil bureaucrats at the local level. With the subsequent "civilianisation" of the regime, former CSP officers were posted to different districts and divisions. In 12 of the 19 districts, the Deputy Commissioners were CSP officers. In all four divisions, Zia appointed former CSP officers as Divisional Commissioners.

Modernisation of Bangladesh includes giving it an Islamic identity, removing martial law and restoring multi-party politics

Two months after his BNP won the general election, on 9 April 1979, President Zia lifted martial law through the enactment of the Fifth Amendment Act to the Constitution of Bangladesh. He also gave the Constitution a more religious outlook and, controversially, legalised the indemnity act thereby validating all actions from 15 August 1975 - the day Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated - to 9 April 1979.

The beginning of General Zia's rule was also the period when all references to Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his role in Bangladesh's history would be papered over. As president and martial law administrator, Zia would tamper with the constitution through replacing its invocations to secularism and Bengali nationalism.

During this period President Zia made a number of valuable contributions to extricate the country from the dire situation it was in at the time he took over. Zia began to actively encourage the development in the countryside by introducing Gram Sarkars (Village Governments) and offering the people a 19-point socioeconomic program. The Gram Sarkar was a 11-member committee tasked with a number of local activities, including resolving family disputes, encouraging population control, promoting food production, and maintaining law and order. By December 1980, 6,800 Gram Sarkars had been organised throughout the country.

Ziaur Rahman also promoted a more humble lifestyle compared to his predecessors and continued to live in a rented home in the Dhaka Military Cantonment, where he had resided since 1972. But he stopped wearing his military uniforms in public and insisted on being called 'President Zia' rather than 'General Zia'. With the passage of time Zia began to relax the security forces around him. When he was Deputy Martial Law Administrator and President (November 1975 - April 1977) the security around Zia was formidable and two major coup attempts against him - in June 1976 and September/October 1977 - were brutally suppressed.

Zia was most frequently criticised by his opponents for being brutal, ruthless, cold and authoritarian; but his death was intimately related to a self-imposed relaxation of the security apparatus around him and to almost naive belief in his powers of persuasion. In the vast majority of the new nations of Asia and Africa leaders become more autocratic and less accessible the longer their regimes last... he was moving significantly towards civilianisation and democratisation.

Through the formation of his political party (BNP) and using the 19-point program as its ideological platform, Zia increased his control over the political process and, at the same time, seemed to relinquish some control by establishing a parliament.

Ziaur Rahman laid the foundation of modern Bangladesh.

Zia re-established democracy and freedom of press in the country as he wanted to build a self-dependent Bangladesh. [Now] Some quarters are trying to assassinate his character as Ziaur Rahman managed to achieve success in the fields where they utterly failed.

Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan, BNP general secretary

Ziaur Rahman made great efforts to civilianise his rule but the real custodians of power continued to be the military. Some local units of BNP were distrusted by army men and were frequently singled out as 'nests of corruption'. At the same time, serious opposition to his governance emerged from the JSD and Awami League, who still had a countrywide base.

As Zia hastened his civilianisation process, many in the armed forces again feared the they might become too powerful and less amenable to military. Zia's quest for civilian legitimisation inevitably distance him from the armed forces which were averse to sharing a sizeable proportion of the resources to which the state had access. Underlying the restiveness of the military in the face of the establishment of the ruling party (BNP), were two other major factors - the resentment of the military against the bureaucracy taking off more and more of the surplus, aid money and other resources under the new dispensation and the political consequences of the inter position of a civilian structure of authority in the hinterland, where the military had become accustomed to regarding itself as the direct extension of the state power.

Charu lata Singh, author of "Media Military and Politics: A Study on Bangladesh" (2010)

Perhaps he [Zia] wanted to shift his power base from a military-bureaucratic-industrial combine to a mass-oriented institutional frame. According to this interpretation, the deaths of Zia and Manzoor can be attributed to a much larger conspiracy. This view suggests that opponents of a critical change are determined to maintain the status quo, that is, the domination of a political life by the combined military, bureaucratic, and entrepreneurial elites.