Deteriorating relationship with Sheikh Mujib

Last updated: 10 October 2017 From the section Tajuddin Ahmad

Campaign for the immediate release of Bangabandhu from Pakistan's jail

Upon returning to Bangladesh, Tajuddin Ahmad immediately focused on reconstructing the countryside and waging a diplomatic war for the early release of Bangabandhu. He began the diplomatic negotiation for the swift return of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman while simultaneously sending useful directions to the administration even before coming to Dhaka from his Calcutta office.

Another incident I recall was on the evening of 4 January 1972 (coincidentally on that day I was a thirty-eight-year old keen civil servant), I accompanied the then Foreign Minister Abdul Samad Azad to the residence of Mr. Tajuddin Ahmed, the Acting Prime Minister of Bangladesh. The purpose was to get his approval of the brief for the Foreign Minister's visit to New Delhi in which I had accompanied him and which was to commence the next day. As I sat and listened with admiration, the Acting Prime Minister's one and a half hour discussion of the brief, I could appreciate his grasp and deep understanding of the socio-economic and political problems that we were then facing.

As we stood up to take leave, I recall his parting words on that occasion. He said, "Remember, the most important duty for you is to impress upon the Indian government to help us build up international pressure for securing Bangabandhu's release from Pakistan. We need him urgently for keeping the nation together". Mr. Tajuddin Ahmed represented Bangabandhu, (who had, on his return from Pakistan, taken over as Prime Minister by then) at the Indian Republic Day celebrations in New Delhi on 26 January 1972. On his return to Dhaka from Delhi he was confronted at the airport with a protocol mess up, when his car did not turn up in time to receive him. Later when I, as the Chief of Protocol regretted this incident, he looked up, smiled and said "I know it was not your fault, but that of my Ministry. But never mind, we learn from experience". I say to my young civil servant friends of today, maybe, we in our time served superior political masters!

Hands over PM role to Sheikh Mujib

Following Bangladesh's victory Tajuddin Ahmad directed the affairs of the state until Sheikh Mujib's famous return.

Under pressure from the international community, President Zulfikar Ali Bhutto released Sheikh Mujib from jail in Pakistan on 8 January 1972. Two days later, on 10 January 1972, after a quick detour of UK, Bangabandhu returned to his beloved Bangladesh to a demi god's welcome. He was met at Dhaka’s Tejgaon airport by a very emotional Tajuddin Ahmad and a host of other prominent people including Colonel Osmani.

Father of the Nation, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, was released from the prison of Pakistan, primarily due to Tajuddin’s relentless efforts, on national and international levels, to ensure his safety and release. Tajuddin knew that a liberated Bangladesh would pave the path toward his release and ensure his return to the soil of an independent nation.

The love and affection of Tajuddin Ahmed for his leader is visible in the video clip of Bangabondhu's arrival at the Dhaka airport. It shows an overjoyed and highly excited Tajuddin Ahmed, with tears of joy in his eyes, fondly stroking Bangabondhu's face like a child does to his father!

On 12 January 1972 Tajuddin Ahmad officially handed over the Prime Minister's position to the Jathir Jonok (Father of the Nation). When asked about his reaction, he was all smile.

It is the happiest day of my life.

Tajuddin Ahmad told journalists on transferring the premiership to Sheikh Mujib,

"Probably the best Finance (and Planning) Minister in the world"

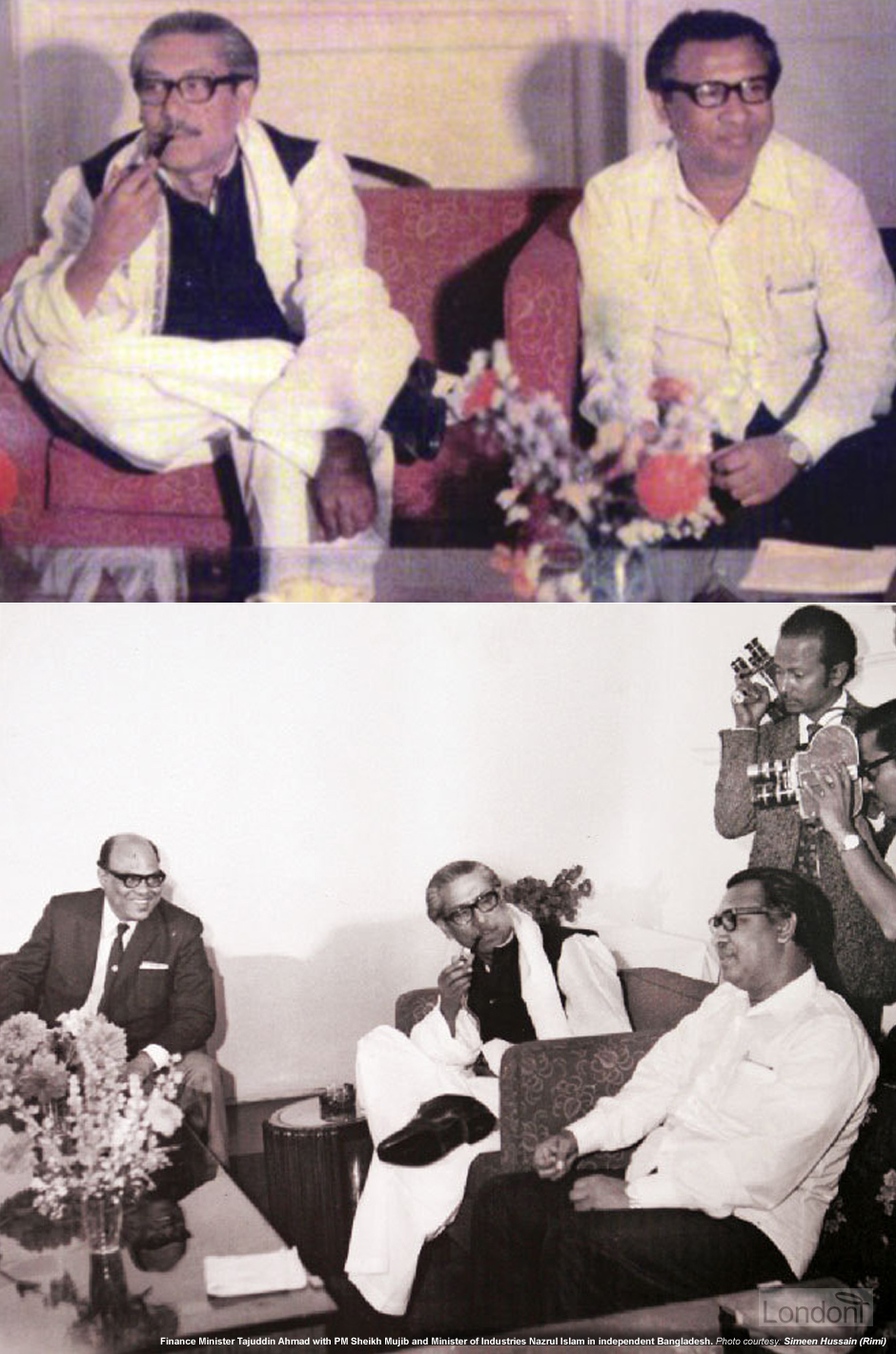

In return for handing over the Prime Minister role, Tajuddin Ahmad was appointed the Finance and Planning Minister. It was left to him to rebuild a broken nation. He began by being member of the team which formulated the first Constitution of Bangladesh.

After the independence of Bangladesh Mr. Tajuddin became the Minister of Finance and Planning, and I became the Deputy Chair of the Planning Commission. We used to meet every day, and over time became very close to each other. He used to treat me like a younger brother, with great warmth, courtesy and respect. We seemed to be always discussing something. In official matters, I think he was the most efficient, and by far the sharpest man I have ever seen. Perhaps in the political arena also he was the one with the best brain, and the one with the sharpest wit and judgment. His analytical skills were exemplary. On a purely human level, undoubtedly, he was a man of high caliber. I cannot over-emphasize the tremendous respect I had for this man. I don’t know anyone who could get straight into the heart of a problem as well as he could, and explain it to others with as much clarity. There were a lot of occasions when we had to work with other ministers in the cabinet on matters of strategy. But Mr. Tajuddin’s analysis, his masterful handling of points and counterpoints, his instincts, were by far the best.

Nurul Islam, former Deputy Chair of the First Planning Commission of Bangladesh

As a minister, he never liked to be dictated by the civil servants. Once I heard him telling a senior civil servant: "Please do not tell me what I should do. As a civil servant, your duty is to give me the options with their merits and demerits. Let me take the decision on my own".

Mr. Tajuddin was a man of great discipline. He did politics all his life yet was extremely meticulous about discipline. He’d say: "When I’ve allotted a certain amount of time to somebody, no one else will be allowed to come near me during that time. X will be with me on X’s time, Y on Y’s. While I’m working in my office there will be no political business, no interviews. I’ve told the Prime Minister never to call me on my office time, unless it is an extreme emergency. I even told him not to schedule any meetings during office hours. We simply do not have time to spare. We have a country to build".

This business of building the country was the most recurring theme in his everyday talk.

"We have to do a lot of work to build this country," he’d keep saying. And he’d tell his officers: "You see gentlemen, it is time to build a nation; time for a lot of work, and definitely not for waste." His standard instruction to Mazhar was: "You’ll allocate different slots of time to different people who want to see me, and you’ll be very vigilant about who gets how much. If you face any problems there, just talk to Mr. Chowdhury; whatever he decides, will be final." Mazhar would indeed come to me at times for help, and I’d sort things out for him. Mr. Tajuddin had a great deal of affection for Mazhar. But even Mazhar was an "apni" to him (and not a "tumi").

Abu Sayeed Choudhury, Private Secretary of Finance Minister Tajuddin Ahmad (1972 - 1975)

He took great pains to build up a self-reliant and flourishing economy. He left a high mark as the Finance Minister of a newly independent nation.

As a member of the constitution framing committee, Tajuddin was one of the key architects in framing the constitution of the newly liberated country. His pragmatic approach to problem solving and stand for truth and justice won him many friends. It also won him enemies who relentlessly conspired to put obstacles in his path.

Tajuddin's passionate vision of a self-reliant Bangladesh

Mr. Tajuddin Ahmed, sitting in that famous Mercedes, pulled me up alright on another occasion, in his inimitable gentle and soft style. I was accompanying him to Heathrow Airport and the car had the national flag flying. At one stage, Mr. Tajuddin Ahmed said, "Mr. Choudhury, I want to point out to you an impropriety in the manner that the flag has been flown. The flag is fitted into the flag pole with a strong piece of white cloth border. This is not permissible, as the colour white is not prescribed in the approved design of our national flag. Please make sure that this is corrected." I must have blushed in shame, accepted my responsibility and said, "Sir, I'm sorry this will not happen again." "I know," he said reassuringly.

Faruq Choudhury, a former civil servant

I remember the first time we went to Washington to attend a meeting of the World Bank. That was in September 1973. We were very low in state funds at that time. We had to count on pennies. On top of that there was Mr Tajuddin’s national aversion to any kind of luxury. After a while he said: "Let’s find a cheap place to eat". So I took him to a cheap restaurant. I was with him on many of his trips around the world. He was always like that; always choosing simplicity over pomposity.

Once we were returning to our office building in the Secretariat after a Cabinet meeting. My office was one floor immediately below his. The building gates were always manned by Security Guards. The Guard refused to let Mr Tajuddin in unless he showed his ID card. I was appalled, so rushed to intervene: "What are you doing young man, he is our Economic Minister". Poor fellow wouldn’t stop apologizing. But Mr Tajuddin was perfectly natural, did not take any offense at all. He just smiled sweetly, and went back to what we were talking about. I am mentioning this to emphasize how different he was from other ministers. Any other minister at a comparable rank would let himself be accompanied by a host of assistants including the Private Secretary; but not Mr. Tajuddin. He was an extraordinary man moving like an ordinary man.

The Liberation War was a very touchy subject for Mr. Tajuddin. He’d get quite emotional at the very mention of the word. It was quite obvious from the way he talked how deeply and totally committed he was to the war efforts. His standard phrase was: Liberation War is our pride, our inspiration.

Mujib Bahini's and Khondaker Moshtaque's long-standing grudge against Tajuddin continues

The intolerance toward Tajuddin and the disrespect of the first Bangladesh government shown by a quarter inside Awami League during the previous year's Muktijuddho continued in post-independent Bangladesh. They were adamant of establishing single leadership in Bangladesh with Sheikh Mujib at helm and eliminating Tajuddin Ahmad. Among these detractors were four leaders of Mujib Bahini who conspired to create a distance between Sheikh Mujib and Tajuddin. They presented Tajuddin negatively to Sheikh Mujib behind his back.

Ek neta ek desh, Bangabandhu Bangladesh. [One leader one country, Bangabandhu Bangladesh].

This type of slogan chanted by a section of Awami League members destroyed the unity of the party

Their negativity had the desired effect.

Sheikh Mujib also began to listen to people like Khondaker Moshtaque Ahmed more and more and consult them instead of Tajuddin Ahmad.

Towards the end of March 1972, according to a hot rumour making the rounds in Dhaka, Sheikh Mujib was grossly overworked and 'in the interests of health and administrative efficiency' was about to re-appoint Tajuddin Ahmad as Prime Minister. Sheikh Mujib, it was said, would step down to reorganise the Awami League and act the Father figure. When I asked Tajuddin about it, his answer was precise and telling: "Someone is trying to cut my throat". Mujib's own reaction to my inquiries was equally severe: "Nonsense," he told me, "do they think I am not capable of running the government?" The rumour, which was obviously inspired by interested quarters, had the desired effect. Henceforth, Sheikh Mujjib was all the more suspicious of Tajuddin and had him carefully watched.

Anthony Mascarenhas, author of "Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood" (1986) and one of the few foreign journalist to enter Bangladesh in 1971

He was clearly not happy at being relegated to the job of finance minister once Bangabandhu took charge as prime minister, but his acute sense of loyalty precluded demonstrating any hint of his displeasure. Discipline was a lesson he had learned early on in life.

And yet, somewhere between cobbling the Mujibnagar government into shape in 1971 and making his way out of government in 1974, Tajuddin became a lonely traveller.

Tajuddin’s loneliness took on newer dimensions in early 1972. The men who had never forgiven him for taking control of the liberation struggle now drove a wedge between him and his leader.

Differences between Sheikh Mujib and Tajuddin Ahmad grows rapidly

Other key issues on which Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and Tajuddin Ahmad stood on the opposite end of the spectrum were the bilateral relationship with USA and other capitalist countries, role of freedom fighters within the new political structure of Bangladesh, and dependency on foreign aid and import.

The division between Bangabandhu and Tajuddin was most tragic incident in the history of our country.

Muhammad Zafar Iqbal, famous writer and professor

Tajuddin Ahmed brooked no nonsense. He tolerated no sycophancy. And he was not squeamish about making his thoughts on politics public, loud enough for everyone to hear. In spring 1974, he warned of looming danger: those who argued that Bangabandhu ought to have more powers were only planning to isolate him from the masses. An isolated man, he told his party men, was a lonely man. And a lonely man could easily be pushed aside. That was Tajuddin, nine months before January 1975.

As I said before, the greatest tragedy of Bangladesh was the chasm that was created between Mr. Tajuddin and Bangabandhu. I strongly believe that but for this unfortunate falling out between the two leaders the history of Bangladesh would have been quite different today. Those two were a perfect duo for our nation, if they would be always together, working together, planning and making bold decisions together, then without a doubt, Bangladesh would by now be well on its way to becoming the cherished land as dreamed by our people in the liberating spirit of the War of Liberation. But alas! Our unfortunate land had, instead, to witness the most devastating spectacle of the terrible split between the two, which eventually led to the end of all our hopes and aspirations.

Sheikh Mujib ask him to resign from cabinet

The vested group surrounding Sheikh Mujib finally succeeded in isolating Tajuddin Ahmad from his long-standing companion. The misunderstanding finally led to the resignation of Tajuddin Ahmad as Minister of Finance from the cabinet on 26 October 1974.

On 13 October 1974, Tajuddin returned to Dhaka following a 37-day foreign trip which included attending the World Bank conference and publicly criticised the government’s economic policies. Two weeks later, on 26 October 1974, Sheikh Mujib telephoned him and asked him to resign "in the greater interest of the nation". Tajuddin was shocked but left quietly. That was the end of his lifelong association with active politics.

Tajuddin never publicly divulged details surrounding the resignation but his silence generated speculation about underlying reasons for Sheikh Mujib’s action.

It was unfortunate that Bangabandhu took the decision to remove Tajuddin, perhaps without verifying the allegations against him. He was hurt by Bangabadhu's decision but never expressed any displeasure against him. In fact, he continued to support Bangabadhu even after that. The history of Bangladesh would have been different today if Bangabandhu had continued to depend on Tajuddin, once his most trusted deputy, for his advice during that difficult period.

Mr. Tajuddin was a truly exceptional man. He left the government, and went straight home. Didn’t grouch or grumble, change sides or parties, switch loyalties, like others do in countries like ours. His loyalty toward his party was unshakable as his love and faithfulness toward Bangabandhu.

As I said before, the greatest tragedy of Bangladesh was the chasm that was created between Mr. Tajuddin and Bangabandhu. I strongly believe that but for this unfortunate falling out between the two leaders the history of Bangladesh would have been quite different today. Those two were a perfect duo for our nation, if they would be always together, working together, planning and making bold decisions together, then without a doubt, Bangladesh would by now be well on its way to becoming the cherished land as dreamed by our people in the liberating spirit of the War of Liberation. But alas! Our unfortunate land had, instead, to witness the most devastating spectacle of the terrible split between the two, which eventually led to the end of all our hopes and aspirations.

Nurul Islam, former Deputy Chair of the First Planning Commission of Bangladesh

Tajuddin Bhai was, in my opinion, the main architect of every major success of Bangabandhu’s political life. Yet the mistake he made by letting himself be talked into losing faith in this man ultimately cost him very dearly.

Let me close by recalling one small story. Once a file was sent by Bangabandhu for Mr. Tajuddin’s approval, Tajuddin Bhai studied the file and wrote in response: "As the Minister of Finance I cannot approve this. I’m sorry that I am unable to comply with your request. Since you are the PM and you have the constitutional right to decide for or against any proposal you may approve it yourself if you so wish. There is no need for my approval."

It was not too long after that Tajuddin Bhai resigned.

Ali Tareq, lawyer and politician was the Public Relation Officer of Finance Minister Tajuddin Ahmad (1972-1974)

In the early 1970s, as Bangladesh's first finance minister, Tajuddin's understanding of the priorities before the nation was without ambiguity. Alone in the cabinet, he believed that Bangladesh's future lay in its use of its human resources. A nation which had gone to war and come back home in triumph could achieve greater wonders. Hence there was little need for the World Bank, for the IMF, indeed for aid from the capitalistic West. He felt it was pointless to speak to Robert McNamara in Delhi in February 1972. And yet, in 1974, when he did see McNamara in Washington, he must have felt the irony of it all. The government he was part of had changed gear, toward the West. He had not. Disillusion had taken over. Only weeks later, he would be out of government. His leader, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, would ask him to resign. The decent man that he was, Tajuddin quietly stepped aside.

Love towards Bangabandhu continues

Even after his enforced resignation Tajuddin bore no ill feelings against Sheikh Mujib. Whenever friends and admirers visited him at his house, he always advised them to support Bangabandhu. Sheikh Mujib too maintained a cordial personal relationship with Tajuddin and his family. He sent a pair of white rabbits for Tajuddin's son Sohel knowing that he was fond of rabbits. Sheikh Mujib personally invited Tajuddin and his family to the weddings of his sons, Kamal and Jamal.

On a day in late October, the call came from the Father of the Nation. Tajuddin Ahmad was as good as his word. He left quietly. Between that low point in his life and the end of life itself, he would lapse into silence. The assault on pluralist democracy, through the rise of the one-party BAKSAL system of government in January 1975, appalled him. It was the statesman in him that informed him of the tragedy ahead. Bangabandhu would destroy himself, he reasoned. And with Bangabandhu gone, Tajuddin and everyone else would be pushed towards doom. And that was precisely the way things happened. As he went down the stairway of his residence in August 1975, a man in army custody, Tajuddin told his wife he might be going away forever. He was to return in November, shot and bayoneted to an ugly death.