Mughal vs English rivalry

With growing hostility between the Mughal officials and East India Company, the Companys’ representatives in Bengal recommended to the court of directors a policy of carrying on trade under the protection of a fortified settlement. The English felt that the threat of force would "oblige the Indians to do them justice". As such in 1685 the Company declared war with the Mughal emperor.

In 1686 the Mughal authorities drove the English from Hooghly after they retaliated when the Mughals refused to allow the English to build a fort in Hooghly.

Shrewd, ambitious, daring, and always watchful of internal political situation in the country, the English thought of carrying on their trade during the second half of the seventeenth century by a show of force; and they also thought of acquiring territorial possessions when possible. In 1669, Sir George Oxenden, the governor of Bombay and the president at Surat, wrote to the Court of Directors of the East India Company: "... the times now require you to manage your general commerce with the sword in your hands".

In 1687, the Court of Directors wrote to the Company’s Chief at Madras, to carry on endeavours for establishing "a large, well-grounded, secure English dominion in India for all time to come". Seeing the signs of decline in the body polictic of the Mughal empire, the English dared to challenge the Mughal authority.

Rise of Kolkata

The hostilities between the two powerhouses continued for few years until in 27 February 1690 they both came to a common resolution. The Company was obliged to pay a fine of £150,000 and to make good the Indian losses. Subsequently, the East India Company’s agent, Job Charnock, established a factory at Sutanuti in August 1690, and six years later built a fort there after the Mughals permitted them to carry on their trade ‘contentedly’ in return for annual payment of Rs 3,000.

Following the decline of the Mughal empire, the shrewd and aggressive European merchants started dabbling in the internal politics of the Indian powers. As the central authority became weak, a number of regional and independent powers emerged in different parts of the country. Though some of those powers, like the Marathas in western India, and the nawabs of Bengal, like Murshid Quli Khan and Alivardi Khan, were fairly strong, the overall political situation was turbulent and chaotic and afforded the ambitious Europeans, notably the English and the French who had already established fortified settlements, excellent opportunities for establishing territorial dominions.

P. N. Chopra, author of “A Comprehensive History of Modern India” (2003)

Job Charnock ()

Job Charnock ()

In 1698, the Company purchased the zamindari (revenue and tax collection) rights of the villages of Sutanuti, Kalighat and Govindpur, allegedly by bribing officials with Rs. 16,000. These villages were part of a khas mahal or imperial jagir or an estate belonging to the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb himself, whose jagirdari rights were held by the Sabarna Roy Choudhury family. Against the wishes of this family and in spite of their protests, the rights over these villages were transferred to the East India Company.

In 1700, the fortified settlement in these three villages was designated as Fort William which was used to station its troops and as a regional base, and later became Kolkata (Anglicized as "Calcutta").

The name of Calcutta is not heard of in the Company's records till 1686, when Job Charnock, the English chief, was forced to quit Hughli by the deputy of Aurangzeb, and settled lower down the river on the opposite bank.

Trading forts or settlements were grandly entitled "presidencies" - tiny footholds where they’re given right by local authorities to protect themselves even by armed force. Kolkata was declared a Presidency City, and later became the headquarters of the Bengal Presidency and capital of the British Indian empire in 1772. The reason behind this decision was the strategically safe location of Kolkata and its proximity to the Bay of Bengal. As a result the center of gravity of trade and commerce in the Bengal province shifted from the town of Hooghly to Kolkata and Hooghly subsequently lost its importance as Kolkata prospered.

Kolkata was Britain's first foothold in Bengal and remained a focal point of their economic activity. It became a major trading port for bamboo, tea, sugar cane, spices, cotton, muslin and jute produced in Dhaka, Rajshahi, Khulna, and Kushtia. The British gradually extended their commercial contacts and administrative control beyond Kolkata to the rest of Bengal.

In fact, India went through a boom of unparalleled proportions as the influx of silver boosted demand for textiles and other goods. And the Company’s shareholders prospered too: annual dividends from the Company’s monopoly control on trade with the East exceeded 25% in the last years of the seventeenth century.

Maritime importance of West Bengal

At the time of Aurangzeb's death, in 1707, the Nawab or Governor of Bengal was Murshid Kuli Khan, known also in European history as Jafar Khan. By birth a Brahman, and brought up as a slave in Persia, he united the administrative ability of a Hindu with the fanaticism of a renegade ??????.

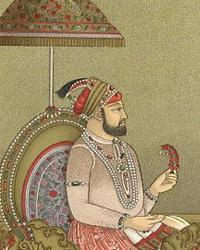

Nawab Murshid Quli Khan ()

Nawab Murshid Quli Khan ()

Up until that point the capital of Bengal had been at Dhaka - or Dacca as it was spelt then - on the eastern frontier of the empire, where the piratical attacks of the Portuguese and of the Arkanese or Maghs could be easily checked. Murshid Kuli Khan transferred his residence to Murshidabad, next to Kasimbazar, which was then the chief emporium of the Gangetic trade. The English, the French, and the Dutch had each factories at Kasimbazar, as well as at Dhaka, Patna, and Maldah. But Kolkata was the headquarters fo the English, Chandarnagar of the French, and Chinsurah of the Dutch. These three settlements were situated not far from one another upon reaches of the Hughli, where the river was navigable for sea-going ships. Kolkata is about 80 miles from the sea; Chandarnagar, 24 miles by river above Kolkata, and Chinsurah, 2 miles above Chandarnagar.

The English built up a string of forts along the coast and had three most important base – Kolkata (in the east), Bombay (now Mumbai, in the west) and Madras (now Chennai, in the south). This gave them military advantage as they can move on all fronts covering India should any major conflict arise.

English abuse exemption from duty payment

In 1717, the Mughal emperor Farrukh Siyar issued a farman and two husb-ul hukms (orders issued by a grand vizier, and second in importance after the farman) by which the East India Company were given its old trading privilege of duty-free trade, and permitted them to rent 38 adjacent villages in Kolkata. Murshid Quli Khan denied permission to the Company to buy the 38 villages. However, the English abused this and caused loss of revenues to the Nawabs.

As the [English] trade grew in opulence, the profit motive outweighed all other consideration. The Company’s European employees had taken employment far from home, in as uncongenial a climate as Bengal’s, because the possibilities of making private fortunes, even on a small salary, were almost unlimited.

Brijen Kishore Gupta, author of "Sirajuddaullah and the East India company, 1756-1757" (1962)

Emperor Farrukh Siyar ()

Emperor Farrukh Siyar ()

The Company allowed its employees to trade on their own account from one part of the Indian Ocean to another, except to and from Europe. This was called the 'country' trade. This concession was also extended to 'free merchants', that is those persons not in the direct employment of the Company, but who were allowed to settle in the Company’s establishments upon securing a license from the Company’s court of directors. A 'privileged' trade was also allowed to the officers of the Company’s shipping, by which they could carry a limited cargo on their ships free of freight. As the trade grew lucrative, it became extremely difficult to check the confines of the 'country' and the 'privileged' trades which were, not infrequently, carried in the monopoly articles. By the beginning of 18th century company turning an annual profit of £0.5 million (now equivalent to £100 million) to be shared between 2,000 stock holders.

It is thus clear that the sources for a conflict in 1756 (Battle of Plassey) had been in existence long before Siraj-ud-Daulah’s accession.

This privilege of carrying on trade virtually free of duties was abused by the servants of the Company for their personal gain. They showed the Company’s dastaks (passes) and claimed exemptions from the payment of duties. This caused loss of revenue to the Nawabs. Consequently, they wanted to collect duties from the English merchants as they did from the Indian merchants, but the English did not care for the Nawab’s wishes and carried on trade on their own terms, if necessary by defying the authority of the Nawab

Mughals vs French

http://books.google.co.uk/books?id=eV262iNGUb4C&printsec=frontcover&dq=battle+of+plassey&hl=en&sa=X&ei=8Wj8T8TkIIPU0QXy8-SpBw&ved=0CDIQ6AEwAA#v=onepage&q=plassey&f=false In 1746, the position of the British and French in the south was that of tenants of land belonging to Indian rulers, held as rent payers and on conditions of good behaviour, recognising the Indian rulers as their overlord. However, in spite of orders of the Nawab of Carnatic to the British and French not to get involved in infighting while under his jurisdiction, the French attacked the English in Madras (presently Chennai) in September 1746. In response, the Nawab sent his son Maphuz Khan with 10,000 men to bring the situation under control. {WHAT HAPPENED NEXT? - MUGHAL LOSE TO FRENCH}This was the first major battle fought between a European and an Indian power where the superiority of the European artillery and methods decided the issue; it was the forerunner of many such battles on the canvas of India. The European powers, who had until now been the vassals of Indians, had turned the scale and from that time onwards history was to record that it was Europeans who were destined to be the landlords and Indians their tenants. The prestige and morale, which is always an important factor in deciding the course of any battle, were transferred from the Indians to the Europeans and as such all subsequent battles between them were half won by the former even before they had been fought.

Seven Years' War of English vs French

By the early 18th century, the British East India Company had a strong presence in India with 23 factories. The major factories became the walled forts of Fort William in Calcutta, Fort St George in Madras, and the Bombay Castle. These stations were independent presidencies governed by a President and a Council, appointed by the Court of Directors in England. The British adopted a policy of partnering up with various princes and Nawabs, promising security against rebels in return for concessions and favours from the Nawabs. By then, all rivalry had ceased between the BEIC and the Dutch or Portuguese. Their only major fierce European rival was the French East India Company established under Louis XIV. The French had two important base in India - Chandernagar (now called Chandannagar) north of Kolkata, and Pondicherry on the Carnatic coast (south eastern coast of India).

By 1756, the East India Company had not only established a flourishing trade in Bengal but had also come to occupy the status of a zamindar, having administrative powers within the territories of Kolkata and over 38 adjacent villages granted as a firman by Mughal Emperor Farrakh Siyar in 1717. The Mughal governorship of Bengal however remained unstable due to the gradual disintegration of central Mughal authority, frequent invasions of Marathas and blows dealt by Nadir Shah.

The Company was just as adept at playing politics abroad. It distributed bribes liberally: the merchants offered to provide an English virgin for the Sultan of Achin’s harem, for example, before James I intervened. And where it could not bribe it bullied, using soldiers paid for by Indian taxes to duff up recalcitrant rulers. Yet it recognised that its most powerful bargaining chip, both home and abroad, was its ability to provide temporarily embarrassed rulers with the money they needed to pay their bills. In an era when governments lacked the resources of the modern tax-and-spend state, the state-backed company was a backstop against bankruptcy.