Aftermath II

Insulting legacy

Because of his treachery Mir Jafar is known by the Indians as Gaddar-e-Abrar ('The Traitor of Faith'). In Bangladesh, he is reviled and the word 'mirjafar' in Bengali is the ultimate insult, denoting treachery of the highest level.

------------ Mir Jafar became the Nawab of Bengal two times. First he ruled from 1757 to 1760 AD, then from 1760 to 1763 AD his son-in-law Mir Qasim was the Nawab. Again he became the Nawab on 25th July 1763 AD till his death on 17th January 1765 AD. He was buried at Jafarganj Mokbara.The field of Plassey no longer exists. The village is also much further from the river. What has remained is the memory of that traitor who helped the English become the lords of Bengal. After Plassey it was the Company at Calcutta and not the Emperor at Delhi, who appointed the Nawab or Subedar of Bengal.

Collapse of the East India Company

Decline of the Nawabs

After the grant of the Diwani of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa by the Mughal emperor Shah Alam II to the BEIC in 1765 and the appointment of Warren Hastings by the East India Company as their first Governor General of Bengal in 1771, the Nawabs were deprived of any real power, and finally in 1793, when the nizamat (governorship) was also taken away from them, they remained as the mere pensioners of the BEIC.

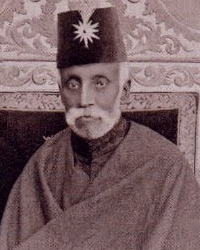

In 1880, Mansur Ali Khan, the last Nawab of Bengal was forced to relinquish his title. His son, Nawab Sayyid Hassan Ali Mirza Khan Bahadur, who succeeded him, was given the lesser title of Nawab of Murshidabad by the British. Hassan's descendants continued the title until 1969 when the last Nawab of the dynasty died. Since then the title has been in dispute.

Mansur Ali ()

Mansur Ali ()  Sayyid Hassan Ali Mirza Khan Bahaduri ()

Sayyid Hassan Ali Mirza Khan Bahaduri ()

Birth of multinationals

The parallels between the East India Company and today’s state-owned firms are not exact, to be sure. The East India Company controlled a standing army of some 200,000 men, more than most European states. None of today’s state-owned companies has yet gone this far, though the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) has employed former People’s Liberation Army troops to protect oil wells in Sudan. The British government did not own shares in the Company (though prominent courtiers and politicians certainly did). Today’s state-capitalist governments hold huge blocks of shares in their favourite companies.

Otherwise the similarities are striking. Both the Company and its modern descendants serve two masters, keeping one eye on their share price and the other on their political patrons. Many of today’s state-owned companies are monopolies or quasi-monopolies: Brazil’s Petrobras, China Mobile, China State Construction Engineering Corporation and Mexico’s Federal Electricity Commission, to name but a few of the mongrel giants that bestride the business world these days. Many are enthusiastic globalisers, venturing abroad partly as moneymaking organisations and partly as quasi-official agents of their home governments. Many are keen not only on getting their government to provide them with soft loans and diplomatic muscle but also on building infrastructure—roads, hospitals and schools—in return for guaranteed access to raw materials. Although the East India Company flourished a very long time ago, in a very different world, its growth, longevity and demise have lessons for those who run today’s state companies and debate their future, lessons about the benefits of linking a company’s interests to a nation’s and the dangers of doing so.